The laboratory rat (Rattus norvegicus), was the first animal known to be domesticated for scientific purposes, being used for the first time in 1828 in a fasting study. In the early 1900’s, the Wistar Institute of Philadelphia and their first female scientist Dr. Helen Dean King, bred the world's earliest “standardised laboratory rat”, known as the Wistar rat.

Today, rats are the third most commonly used animal in scientific research in the UK. Approximately 5% of experiments are carried out using rats. For the most recent figures see Animal Statistics.

Which rats are used in scientific research?

The rat most often used in scientific research is the Wistar rat, which is an albino breed of the common brown rat Rattus norvegicus.. Wistar rats are bred in clinical conditions to ensure genetic standardisation and avoid contamination with pathogens, both of which can affect the results of experiments.

Another rat breed commonly used in scientific research is the Long-Evans rat. Developed by Dr Long and Dr Evans in 1915, the Long-Evans rat is the result of a cross between a female albino from the WISTAR Institute and a wild male (Rattus norvegicus). These rats are outbred, meaning they have a greater genetic variability.

All rats used in scientific research are especially bred for purpose. Wild rats and Fancy or pet rats are not used in scientific research in the UK.

Why are rats used in scientific research?

Rats are one of the most commonly used animals in research because they share many biological and genetic similarities with humans. Rats are also relatively easy to house, breed, and care for compared to larger animals with more complex needs.

Rats have frequently been used in research focusing on cardiovascular diseases, psychiatric disorders, spinal injury, stroke, diabetes, surgery, transplantation, auto-immune disorders, cancer and bone healing. In drug development, rats are routinely used to test the efficacy and safety of potential medicines prior to human clinical trials.

1. Physiological and genetic similarity to humans

- Rats share around 90% of their genes with humans.

- Rat organ systems (cardiovascular, nervous, endocrine, etc.) function in similar ways to ours, making them good models for studying human diseases.

2. Size and practicality

- Rats are larger than mice, which makes certain procedures easier, for example surgery, blood sampling and behavioural tests.

- Despite their size, rats are still small enough to be comfortably housed in groups under controlled conditions.

3. Well-characterised biology

- Scientists have collected decades of data on rat physiology, anatomy, and behaviour.

- Rat-specific tools (genetic strains, disease models, behavioural tests) are widely available.

4. Behavioural research

- Rats are highly intelligent and social, making them particularly valuable in studying learning, memory, addiction, anxiety, and other neurological or psychological conditions.

- The ability of rats to perform complex tasks sets them apart from other species, such as mice, in behavioural science.

5. Disease models

- Rats are used to model many human conditions such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and spinal cord injury.

6. Advances in genetics

- Historically, mice overtook rats in genetic research because mouse genetics were easier to manipulate. However, recent advances, such as CRISPR-Cas9, have made genetic engineering in rats much more straightforward, reviving their importance for genetics.

7. Ethical and regulatory considerations

- Using rats helps reduce the use of animals with more complex needs, such as primates or dogs, in many areas of research.

- They allow researchers to test the safety of potential treatments before moving into human trials.

Research case studies: rat

University of Oxford - Deep brain stimulation to treat Parkinson's

Deep brain stimulation, where electrical pulses are delivered to specific structures deep in the brain, is an effective treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Improving the treatment requires the ability to test new ways of stimulating, but this is difficult to achieve using people with Parkinson's disease, as it requires considerable resources. One candidate for improving deep brain stimulation is to use a "closed-loop" approach, whereby brain signals are recorded and analysed in real-time for activity that is known to be a marker of disease symptoms. Stimulation pulses can then be timed to coincide with these activities in order to reduce both symptoms and side effects. We used a well-established rodent model of Parkinson's disease to examine a closed-loop approach that was applied using a microchip that could also be used in human stimulation devices. Using these experiments, we were able to demonstrate that our approach could reduce activity associated with Parkinsonian symptoms and change the movement of the rats in predictable ways. This work provides important evidence that closed-loop stimulation could be an impactful technique in human deep brain stimulation and that it can be implemented using technology suitable for human devices.

Imperial College London - Drug cocktail holds promise for spinal injuries

Scientists have discovered a combination of two commonly available drugs that could help the body heal spinal fractures.

The early-stage research in rats, by a group of scientists led by Imperial College London, revealed two existing medications can boost the body’s own repair machinery, by triggering the release of stem cells from the bone marrow.

The team say the two drugs (currently used for bone marrow transplants and bladder control) could be used for different types of bone fractures, including to the spine, hip and leg, to aid healing after surgery or fractures.

When a person has a disease or an injury, the bone marrow (the spongy tissue within bone) mobilises different types of stem cells to help repair and regenerate tissue.

The new research suggests it may be possible to boost the body’s ability to repair itself and speed repair by using new drug combinations to put the bone marrow into a state of “red alert” and send specific kinds of stem cells into action. The researchers used drugs to trigger the bone marrow of healthy rats to release mesenchymal stem cells, a type of adult stem cell that can turn into bone and help repair bone fractures. The two treatments used in the research were a CXCR4 antagonist, used for bone marrow transplants, and a beta-3 adrenergic agonist, that is used for bladder control.

The rats were given a single treatment with the two drugs, which triggered enhanced binding of calcium to the site of bone injury, speeding bone formation and healing.

One of the drugs used in the study was found to trigger fat cells in the bone marrow to release endocannabinoids, which suggests they may have a role in mobilising the stem cells and thereby promoting healing. However, the researchers add that phytocannabinoids (such as cannabis) would not have the same effect, as they act on the brain rather than the bone marrow.

Where do laboratory rats come from?

Animals used in scientific research in the UK are always bred for purpose and do not come from the wild or facilities that breed animals as domestic pets or livestock. The only exceptions occur when pets are volunteered by owners to take part in clinical trials for veterinary medicines and treatments, or when wild animals are studied for conservation purposes. Most facilities that breed animals as domestic pets do not have the strict bio-hazard controls required to breed “clean”, pathogen free, animals for the laboratory. It is also rare for facilities that breed pet animals to be able to provide the appropriate habituation training to prepare an animal for life in the laboratory.

It is exceptionally important that animals destined for the laboratory are free from diseases and pathogens. They must also be habituated to the laboratory environment and regular handling. Larger animals will receive positive-reinforcement training so that they are familiar with basic laboratory procedures such as entering a transport cage.

In the UK, laboratory rats are bred by government licensed and regulated breeders based in the country.

How are rats looked after?

In the UK, we maintain some of the strictest laboratory animal welfare standards in the world. All research animals must be housed according to the minimum requirements laid out by regulators. Different animals require different care, depending on their natural environment and behaviours.

For example, lighting in the laboratory is timed to maintain a natural day/night cycle, the temperature of an animal room is determined depending on what that species finds most comfortable, and animals are provided with species-specific activities and enrichments that stimulate them and enable them to express their natural behaviours. . Many laboratories have cages with automatic watering systems as well as individual ventilation (IVC), ensuring a clean and consistent airflow within the cage.

Facilities in the UK are not allowed to keep animals in cages with grated floors, they must use solid flooring and provide bedding materials that are comfortable for the animal.

Animals in research are cared for by specially trained Animal Technicians.

For best practice guidelines on housing and caring for rats in the laboratory, see NC3Rs Housing and husbandry: Rat.

For the minimum housing requirements by law, see Code of practice for the housing and care of animals bred, supplied or used for scientific purposes.

For more information on housing laboratory animals see The 3Hs Initiative: Housing

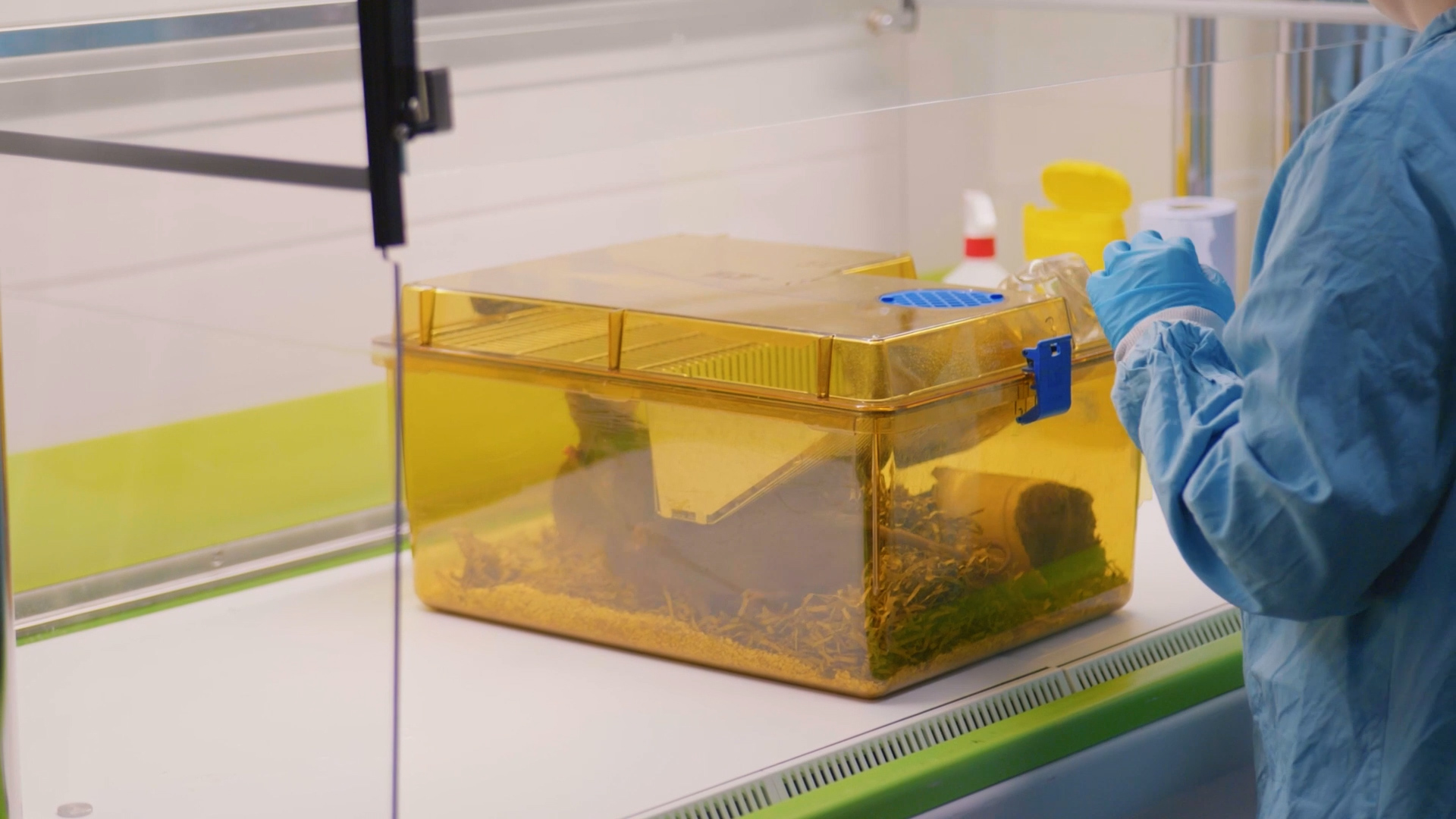

Examples of laboratory rat enclosures

Standard housing for laboratory rats

Below is an example of a standard cage for laboratory rats in the UK which meets the minimum enclosure requirements as set out by the UK Home Office.

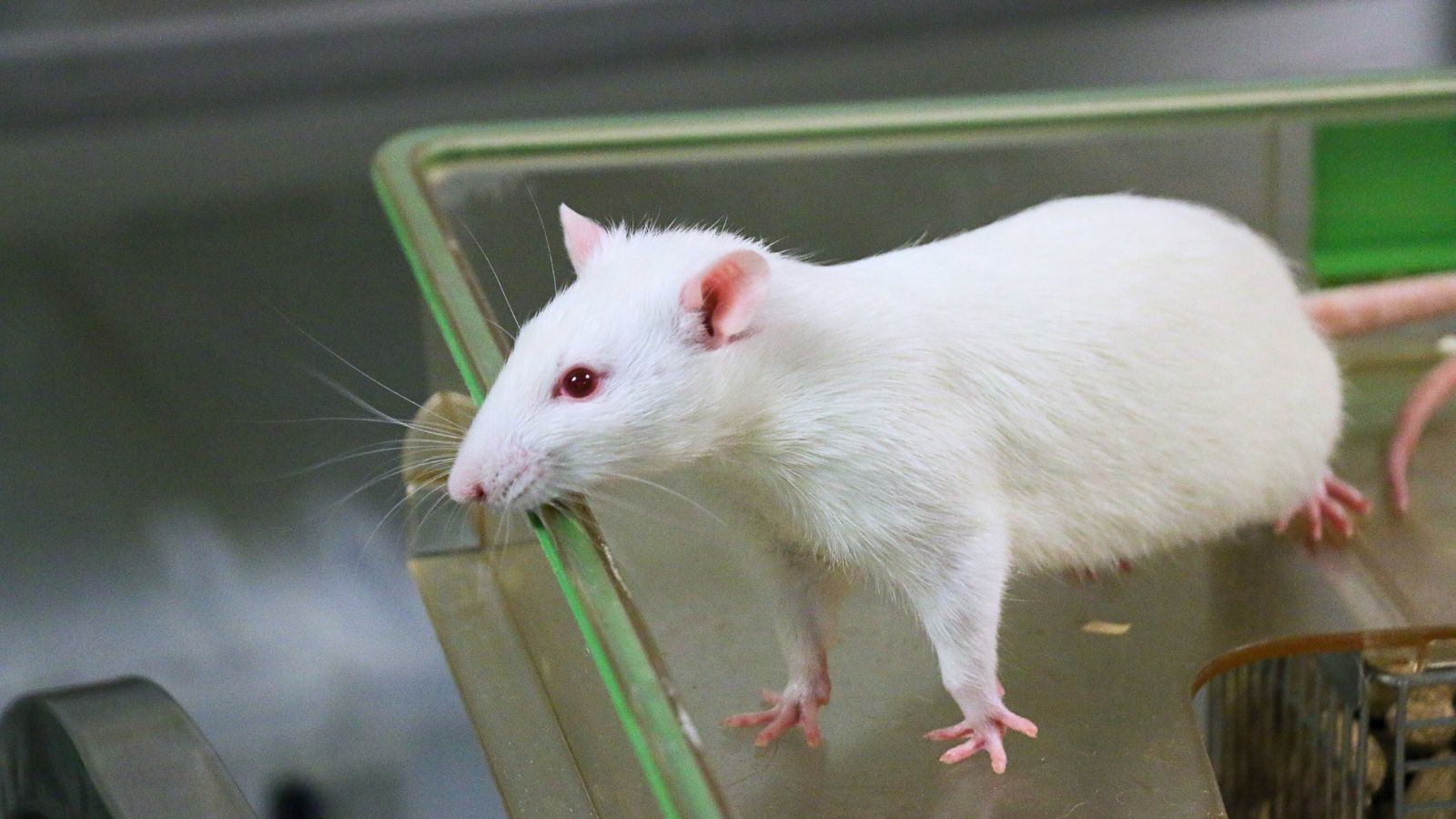

Image above: rats inside a standard laboratory cage for the UK ©Understanding Animal Research

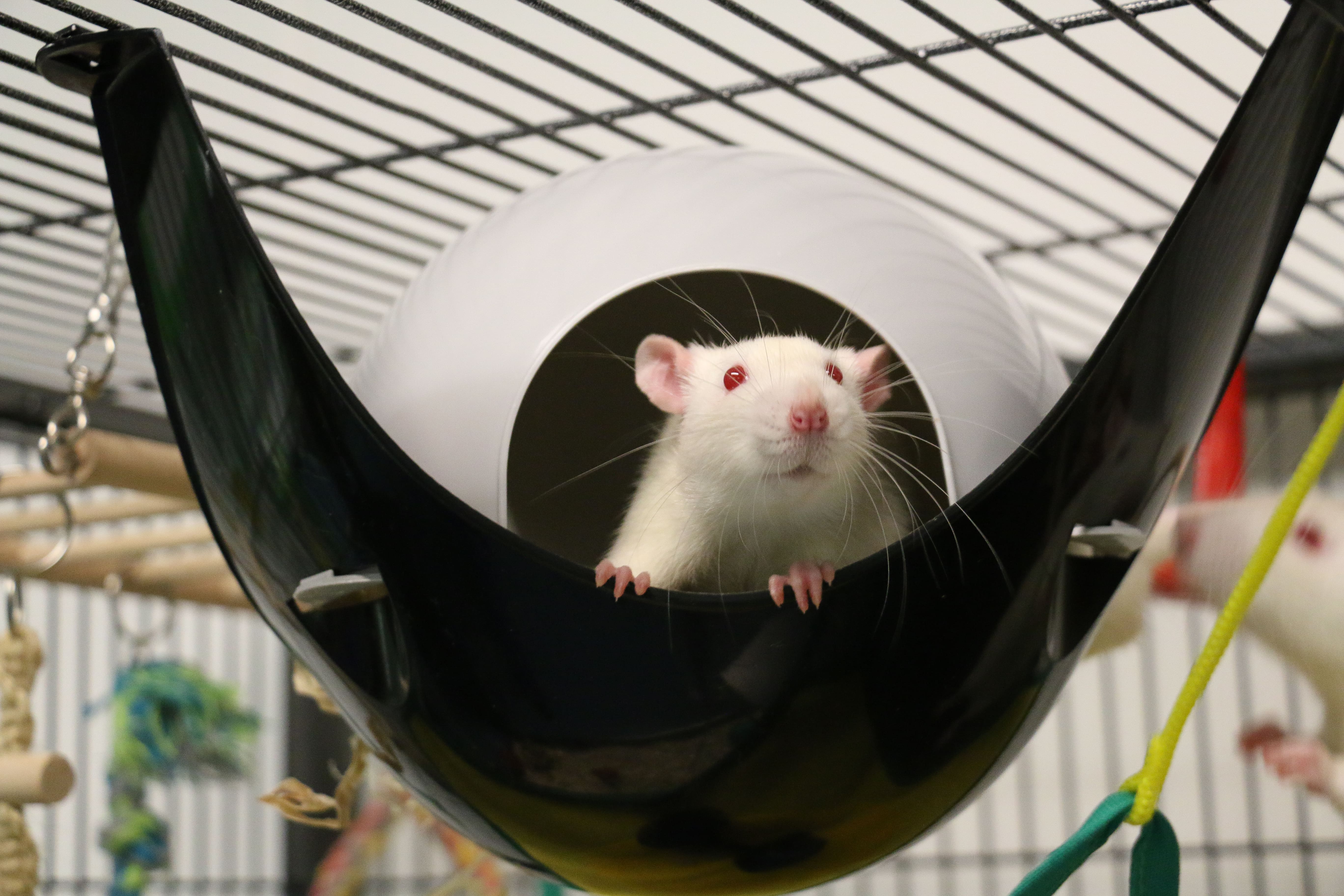

Play pens for laboratory rats

Some research facilities provide their rats with play pens as a form of environmental enrichment. Rats are given access to the play pens once or more a week. Play pens include multiple levels, opportunities for climbing, and lots of rat friendly toys.

Image left: rats in a playpen at the University of Manchester ©Understanding Animal Research

Image right: Close up of rat in playpen at the University of Manchester ©Understanding Animal Research

Interesting fact: rats “laugh” when they are tickled!

While researching the behaviour of rats, scientists have discovered that they love to be tickled on their bellies. When tickled, rats let out a high-pitched squeaking noise inaudible to human ears, the same vocalisations that they make when playing with other rats.

Read more about tickling rats and the husbandry implications on NC3Rs.

Read more on the science behind rat tickling and how this discovery revealed something new about the brain on Science.

Videos about rats in scientific and medical research

More information about rats in scientific and medical research