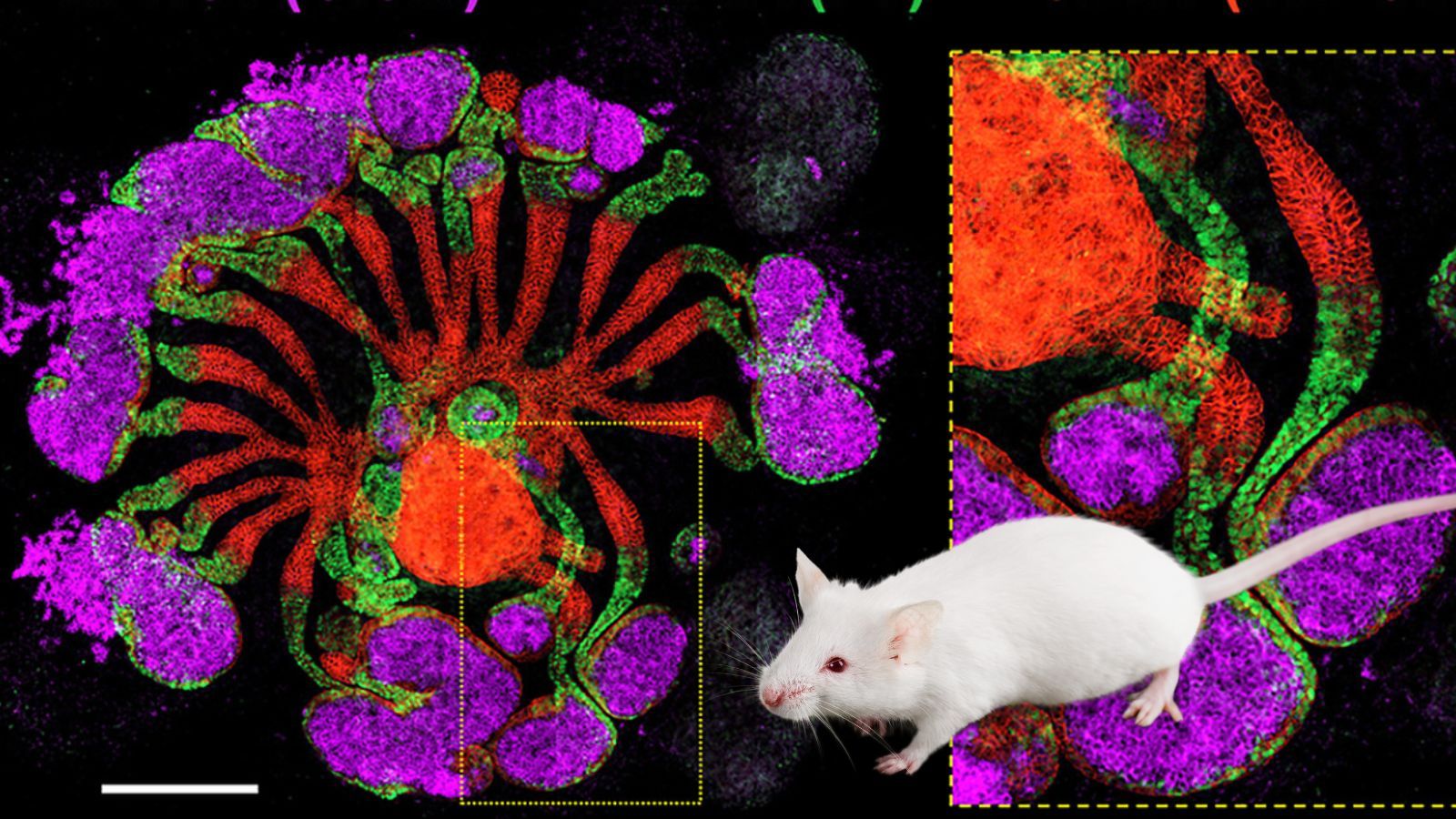

As part of the research effort to develop lab-grown human organs to aid the study of kidney diseases and to mitigate the world transplant organ shortage, scientists have successfully produced the most sophisticated, bio-engineered kidney organoid to date. Organoids are miniature, simplified versions of organs which are grown in three dimensions in vitro in the lab. The newly created kidney organoid was successfully transplanted into mice, where it functioned and produced urine.

Exceeded in complexity only by the brain, kidneys are vital organs that filter the blood to remove waste and excess water. They are also the most in-demand organ for transplants, with long waiting lists. One in seven adults develops kidney diseases. Despite these numbers, the development of novel therapeutics remains limited, in part due to the lack of physiologically relevant human kidney models.

Because they are so complex, scientists have only been able to grow crude approximations of kidneys in the lab until now. A new paper in Cell Stem Cell, describes the most mature, realistic, and complex lab-grown kidney structures to date. Generated from stem cells, these so-called “assembloids” recapitulate some of the sophisticated internal organisation of the kidney, combining the kidney’s filtering and urine-concentrating features.

“You wouldn’t mistake it for a real kidney,” experimental anatomist Jamie Davies told Science, “but it is trying to do the right things.” The advanced kidney organoids showed patterns of gene activity that resembled those of kidneys from new-born mice and released some of the same hormones as true kidneys. When implanted into mice, the 1mm -wide structures readily connected to the rodents’ circulatory systems where they began to filter blood and produce dilute urine.

Compared to previous kidney organoids, “this is probably the best we’ve ever seen,” according to developmental biologist Alex Combes of Monash University. But there’s still “a way to go” before researchers can culture new kidneys for transplantation, he cautions. Notably, the organoids grown from human stem cells didn’t mature as well as their mouse counterparts. Despite being able to link up to the circulatory system of live rodents, they couldn’t produce urine.

The new organoids are already helping scientists study how kidneys develop, function, and fail. Stem cell biologist Zhongwei Li of the University of Southern California and colleagues created similarly complex organoids that carry one of the genetic defects that causes polycystic kidney disease, an inherited illness that can cause the organ to fail. When inserted into mice, the organoids sprouted multiple cysts, like the kidneys of people with the illness.

“This is a revolutionary tool for creating more accurate models for studying kidney disease,” Li said. “It’s also a milestone towards our long-term goal of building a functional synthetic kidney for the more than 100,000 patients in the US awaiting transplant — the only cure for end-stage kidney disease.” Challenges remain, but Li and his colleagues predict they can solve most and have a transplantable kidney replacement ready for animal testing within five years.

Article image: composite created using Huang et al, Figure 4. Assembly of spatially patterned hKPAs from iNPCs and iUPCs, Spatially patterned kidney assembloids recapitulate progenitor self-assembly and enable high-fidelity in vivo disease modeling

Last edited: 16 January 2026 11:35