Polio was once a disease that devastated communities across the world. It spreads easily through contaminated food and water and in severe cases leaves children paralysed for life. While most people survive polio without any symptoms, for some it can severely damage their nervous system and their ability to move their muscles, including the ones required to breathe. This led to a mortality rate in the region of 10% of those suffering paralytic symptoms.

Polio has been around for most of human history with prehistoric remains and ancient carvings depicting people who display symptoms which match what we expect of the disease. However, the poliovirus itself wasn’t discovered until 1908 when researchers Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper used monkeys, mice and rats to demonstrate how it spreads. This discovery was the beginning of a long scientific effort spanning over a century which has now brought us to the verge of eradicating the disease once and for all.

Mankind’s Early Attempts at Polio Vaccines

Before we had the tools to properly study viruses, early attempts to create a vaccine against polio were primarily based on trial and error. In 1935, without modern standards for animal testing and safety regulation, vaccines developed by Maurice Brodie and John Kolmer were rushed into human trials. The results were disastrous, and several children suffered acute paralysis. At least five died following vaccination, although it remains unclear whether their deaths were the result of improperly inactivated virus or simply a lack of effectiveness.

Before we had the tools to properly study viruses, early attempts to create a vaccine against polio were primarily based on trial and error. In 1935, without modern standards for animal testing and safety regulation, vaccines developed by Maurice Brodie and John Kolmer were rushed into human trials. The results were disastrous, and several children suffered acute paralysis. At least five died following vaccination, although it remains unclear whether their deaths were the result of improperly inactivated virus or simply a lack of effectiveness.

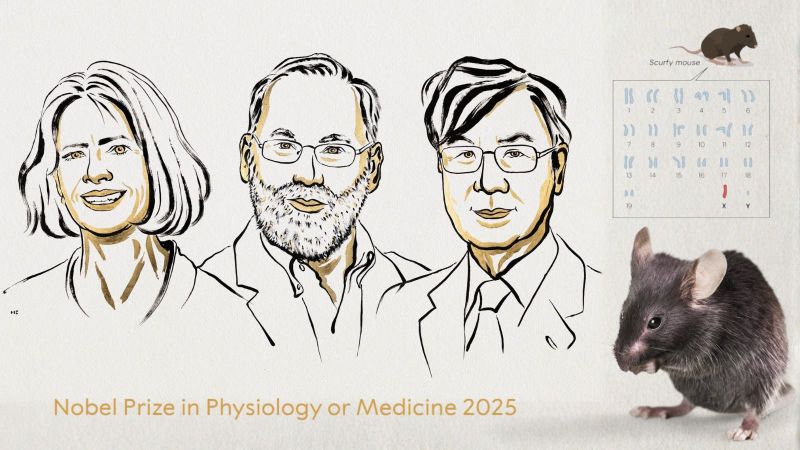

By the 1940s, polio was paralysing or killing approximately half a million people every year worldwide. Although now disputed, it was widely believed that even US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt was a survivor of the illness, having lost the use of his legs in the 1920s. It was clear that major advancements in prevention were needed to protect public health. The necessary breakthrough came in 1948 when a team of researchers comprised of John Enders, Thomas Weller and Frederick Robbins were finally successful in growing the virus in non-nerve human tissue – a revolutionary development which jointly earned them the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1954. As technology to visualise things as small as viruses had not yet been developed, they had to demonstrate the effectiveness of their technique by injecting mice and monkeys with the virus they had grown to show that they would develop polio. The breakthrough meant that it was now possible to grow large amounts of virus. This was a gamechanger that paved the way for the successful development of polio vaccines.

Photo right: Franklin D. Roosevelt in wheelchair, FDR Presidential Library & Museum photograph by Margaret Suckley, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Salk and Sabin: Two Vaccines We Still Use Today

Following the groundbreaking work from Enders, Weller, and Robbins, research into the virus could be conducted on a much larger scale. As a direct result of this, two researchers, Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, would go on to create the polio vaccines that we still use today, albeit with much less involvement of animals. The approaches of Salk and Sabin were very different, but both relied heavily on the use of animals to make their discoveries.

Salk’s Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV)

In 1954, Salk’s Inactivated Polio Vaccine became the first successful polio vaccine in human history. It used the principle that an inactivated (killed) virus would be sufficient to teach the body how to recognise and fight against a real infection. To do this, he grew the virus within the kidney cells of live monkeys, where they grew extremely well, then inactivated the virus with a chemical called formaldehyde. In 1954, the Salk vaccine was tested in what remains one of the largest medical trials in history, involving over 1.8 million children across the United States. The results were clear: the vaccine was safe and effective for all three strains. Yet there were drawbacks. The immunity Salk’s vaccine provided waned over time and every million doses required the sacrifice of around 1,500 monkeys, on top of the many animals required in research and development. This is because stable, continuous cell lines didn’t exist at the time, so cell culture experiments required cells from a live animal. It wouldn’t be until the 1970s when Vero cells would be used to do this work, and the 1980s when regulatory approval followed.

Sabin’s Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV)

Albert Sabin believed that these issues could be remedied with a weakened-virus vaccine as opposed to inactivated virus. Sabin’s Oral Polio Vaccine is made by passaging the virus multiple times through monkeys and cell cultures, selecting for strains which can infect the gut, but not the nervous system. This approach made a virus which was able to replicate enough to train the immune system, but not enough to cause disease. While his vaccine generated longer-lasting immunity to polio than IPV, Sabin was aware of the costs incurred in terms of animal lives and wellbeing. In a paper he authored in 1956, just four years before approval of OPV, he wrote:

"Approximately 9,000 monkeys, 150 chimpanzees and 133 human volunteers have been used thus far in the quantitative studies of various characteristics of different strains of polio virus. [These studies] were necessary to solve many problems before an oral polio vaccine could become a reality.”

Together, Salk’s and Sabin’s contributions laid the foundation for global polio eradication efforts through two different mechanisms, but none of it would have been possible without extensive safety testing in animal models such as monkeys, mice and guinea pigs before finally beginning human trials.

The Campaign for a Polio-Free World

Following the approval of both Salk’s and Sabin’s vaccines, efforts to eliminate polio became a global public health priority, and both vaccines became integral to the eradication effort.

IPV faced its first major setback not long after its initial approval, a major blow to public confidence due to an insufficiently inactivated batch of vaccine led to around 200 cases of paralytic polio and several deaths. This was known as the Cutter Incident, as the batch had been produced by Cutter Laboratories. It became a major task for the medical community to restore faith in vaccines and this was accomplished through stricter safety protocols as well as public displays of confidence, most famously when Elvis Presley received Salk’s vaccine on national television in 1956.

Elvis Presley receiving his polio vaccination. Department of Health Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

While IPV was the standard in most wealthy nations, Sabin’s OPV became the foundation of polio eradication efforts in the developing world. As it was administered orally, often on a lump of sugar, it was much easier to give to children and didn’t require expensive sterile needles. It was also significantly cheaper to produce and could be administered by community volunteers rather than trained healthcare workers. However, this came with a rare but serious risk that in some cases the attenuated virus could mutate back into a form that could cause paralysis upon further transmission.

In 1988, the World Health Organization and partners launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) with the aim of eliminating the virus worldwide. Mass OPV vaccination campaigns, sometimes reaching millions of children in a single day, became a hallmark of this campaign, especially across the developing world.

Global Eradication: The Final Hurdle

Thanks to decades of coordinated efforts, polio is now on the verge of being eradicated globally. Only a few cases of wild poliovirus are reported each year, and two of the three naturally occurring strains (type 2 and type 3) have been officially declared eradicated. Type 1 poliovirus is the only wild poliovirus that exists currently and is localised entirely within Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Today, there is increasing, concern about cases of polio caused by vaccine-derived polio virus strains (VDPV), rather than wildtype strains. In 2017, for the first time, there were more cases worldwide of VDPV than wild poliovirus. This called for a change in approach and OPV formulations were developed that were much more stable, preventing the weakened virus from reverting back to a pathogenic form.

Despite its higher cost, use of IPV has become more prevalent in the developing world. It has been used systematically to target outbreak spots to prevent the infection spreading when a case is identified. Animal models for safety testing have been reduced, and now monkeys are not used. Instead, researchers have found ways to test the safety of vaccine batches using transgenic mice expressing human proteins. This method was gradually accepted by different health organisations during the early 2000s and will now likely be the norm until polio is entirely eradicated. While the use of animals is still a necessity, the shift from monkeys to mice demonstrates the commitment of the bioscientific community to minimising animal harm and suffering wherever possible and is an example of the principle of refinement in action.

After more than a century of research, the world stands close to a historic achievement. 20 million people are walking today who otherwise might not have been, and 1.5 million deaths have been avoided in children. Polio will soon enter the exclusive list of diseases totally eradicated by humans, currently only populated by smallpox virus which was also wiped out through vaccination campaigns. There is no question that animal research has been instrumental to this success, both in the development of vaccines and in their regulatory safety testing.

Last edited: 3 November 2025 13:31