Mice, rabbits, frogs and sheep – each took their turn in the development of pregnancy tests.

You want to know if you are pregnant or not? Easy, right? Just buy a cheap and reliable kit from the chemist or supermarket and get an instant answer from a quick urine test in the comfort of your own home. But it wasn’t always so easy. In fact, the creation of the reliable pregnancy tests that benefit so many women, and that now cost just a few pounds, was a scientific battle that was only won thanks to a great deal of animal research and the determination of one extraordinary women.

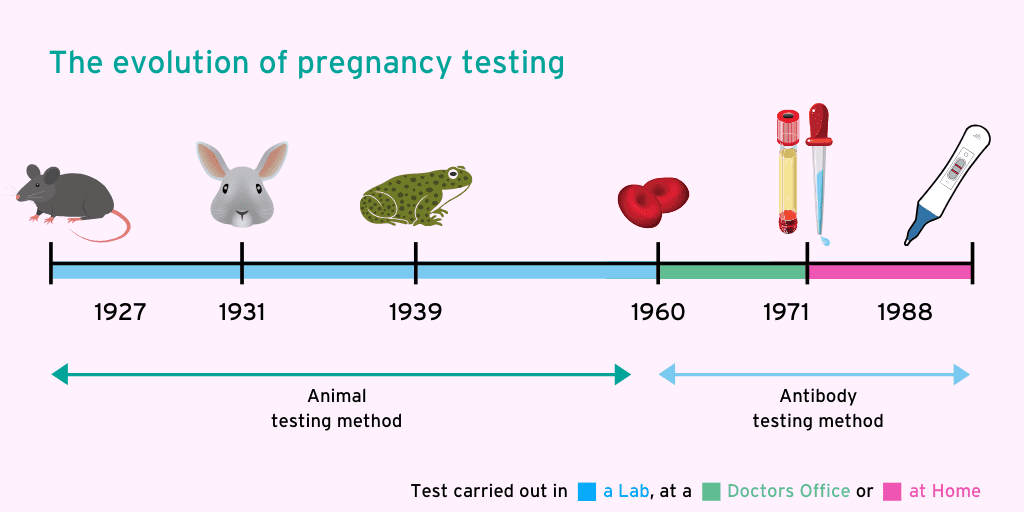

In the early 20th century, scientists were becoming aware of the chemical messengers we now know as hormones. Working on the assumption that some hormones might be found in urine, and that these messenger molecules might be detectable from the responses they produced in animals, the German gynaecologists Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek developed the Aschheim-Zondek, or A-Z, test, in 1927, the first truly effective bioassayto detect early pregnancy.

In the Aschheim-Zondek test, a urine sample was injected into a sexually immature female mouse. If hormones associated with pregnancy were present in the urine sample, the mouse would go into heat despite its young age and the test would be positive.

The Aschheim-Zondek test was effective but complex and unwieldy, needing to be conducted by specialists in a laboratory over a number of days. To be suitable for use in the test, mice needed to be three to five weeks in age and weigh between six and ten grams. For each pregnancytest, three to five of these infant mice were necessary. Each mouse would be injected three times a day for three days and then allowed to rest for two days before being killed so that their ovaries could be examined to look for changes that indicated the presence of the hormone gonadotropin that is produced in early pregnancy, such as enlargement of the ovaries.

The A-Z test was so reliable, with an eventual 98.9% success rate, that it became the benchmark standard for many years, although rabbits replaced mice as the test animal in 1931 because they were easier to work with.

Nonetheless, it was laborious, slow and expensive, requiring the involvement of a laboratory. It would also be some weeks before you received a result. What’s more, it wasn’t as sensitive as modern pregnancy tests and could not detect pregnancies earlier than two weeks. Something better was needed.

That something was, for a while at least, frogs. The British scientist Lancelot Hogben found that an injection of urine from a pregnant woman would stimulate frogs to lay eggs. The frogs that came to be the standard animal used for this purpose – Xenopus leavis frogs from South Africa – are still a stalwart of developmental research today.

Frogs didn’t need to be killed in order to give a result and could, therefore, be reused, lowering test costs. They also gave faster results, usually within twelve hours. Frog-based testing quickly replaced earlier methods and tens of thousands of pregnancy tests were run on frogs after their introduction in the 1940s. But despite improvements in speed, cost and efficiency, the fact remained that the vast majority of women did not have easy access to pregnancy tests.

That would begin to change with the breakthrough discovery in the 1950s of a test that reliably detected a newly-discovered pregnancy hormone, chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), without the use of live animals, although still with a crucial link to animal research. The test was based on bio-engineered sheep blood cells which reacted to the presence of hCG when it was present in a urine sample. It was reliable and quick, giving a result in only an hour or two, and, crucially, it was simple to administer.

In fact, given access to the right kit anyone could do it. So why did it still require the involvement of the family doctor, laboratories and a raft of expensive (and sometimes judgmental) professionals for a woman to find out if she was pregnant? That was the question asked by Margaret Crane a graphic designer working for a pharmaceutical company designing packaging for lipsticks and ointments. She saw how simple the pregnancy test was to administer and saw no reason why women should not be able to do the tests themselves at home, if only the test could be packaged in an appropriate way. And that is what she did, developing a prototype home pregnancy urine test that was simple to administer and gave results in two hours.

When Margaret showed her design to her bosses, however, she discovered that scientific hurdles are sometimes easier to clear than social ones. She encountered general scepticism about the ability of women to self-administer tests, an unwillingness to let go of the lucrative laboratory testing business, and an abiding sense that too much autonomy for women in these matters was in some sense immoral. But she wouldn’t let it go, or be passed by and her determination and persistence was rewarded in 1969 when the first patent for a home pregnancy test was awarded with Margaret named as the inventor, although commercial rights went to the sponsoring company Oregon. That patent would lead to the Predictor Test, launched in Canada in 1971 and destined to change the world.

Today tests are even quicker, cheaper and more reliable and no longer depend on animals or their cells but are based on dye-activated molecules instead. It is impossible to put a price on the value that these tests have had and continue to have for women all over the world. Millions of lives have been changed thanks to a long line of scientists, the crucial contribution of animals, and a graphic designer who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

References

Hillel Shapiro: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59041218

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harold_Harvey_The_Letter_1937.jpg

BBC World Service Witness History, The first home pregnancy test: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3cswsk6

https://www.people.hps.cam.ac.uk/index/teaching-officers/hopwood/xenopus

http://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/pee-pregnant-history-science-

https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/aschheim-zondek-test-pregnancy

Last edited: 30 August 2023 10:23