New-Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and Non-Animal Technologies (NATs)

- Around 69% of funding council money is spent on research methods that do not directly use animals.

- Around 80% of charity funding is spent on research methods that do not directly use animals.

Animal and non-animal methods are both essential to bioscience. They are often both used as part of the same study, with animals used to answer the questions other techniques cannot.

In recent years, technology has advanced rapidly leading to better animal tests, better tools and more non-animal methods. These are adopted alongside the older tools as they become available, and will ultimately replace some of them for most purposes.

In most cases, the non-animal methods has been in development for many years but only recently became usable.

What are NAMs?

NAMs stands for ‘New Approach Methodology’ and refers specifically to the 12% of animal experiments that are for regulatory purposes. These are tests demanded by the regulator to show that a product is safe enough for humans, animals and the environment to use or be exposed to. NAMs are a mix of maturing non-animal technologies and methods newly applied to regulatory questions.

NAMs are distinct to NATs, or non-animal technologies, which can complement and sometimes replace animals in experiments.

Adopting NAMs and NATs

It is illegal to use animals if a non-animal method can be used instead, so adoption in regulatory use has no legal barriers. NAMs are thus being phased-in with a view to understanding where they can replace animals. Outside of regulatory requirements, drug development companies are free to use NAMs and NATs to test or develop their products prior to submitting them for safety testing.

NAMs will not immediately replace existing test methods, but will ultimately avoid current animal and nonanimal tests in some areas. The market for animal test methods and non-animal methods is currently around the same size at around $10Billion each. However the non-animal segment is expected to grow at a rate (CAGR) of 13.5% whereas the animal market will only grow at a rate of 5%.

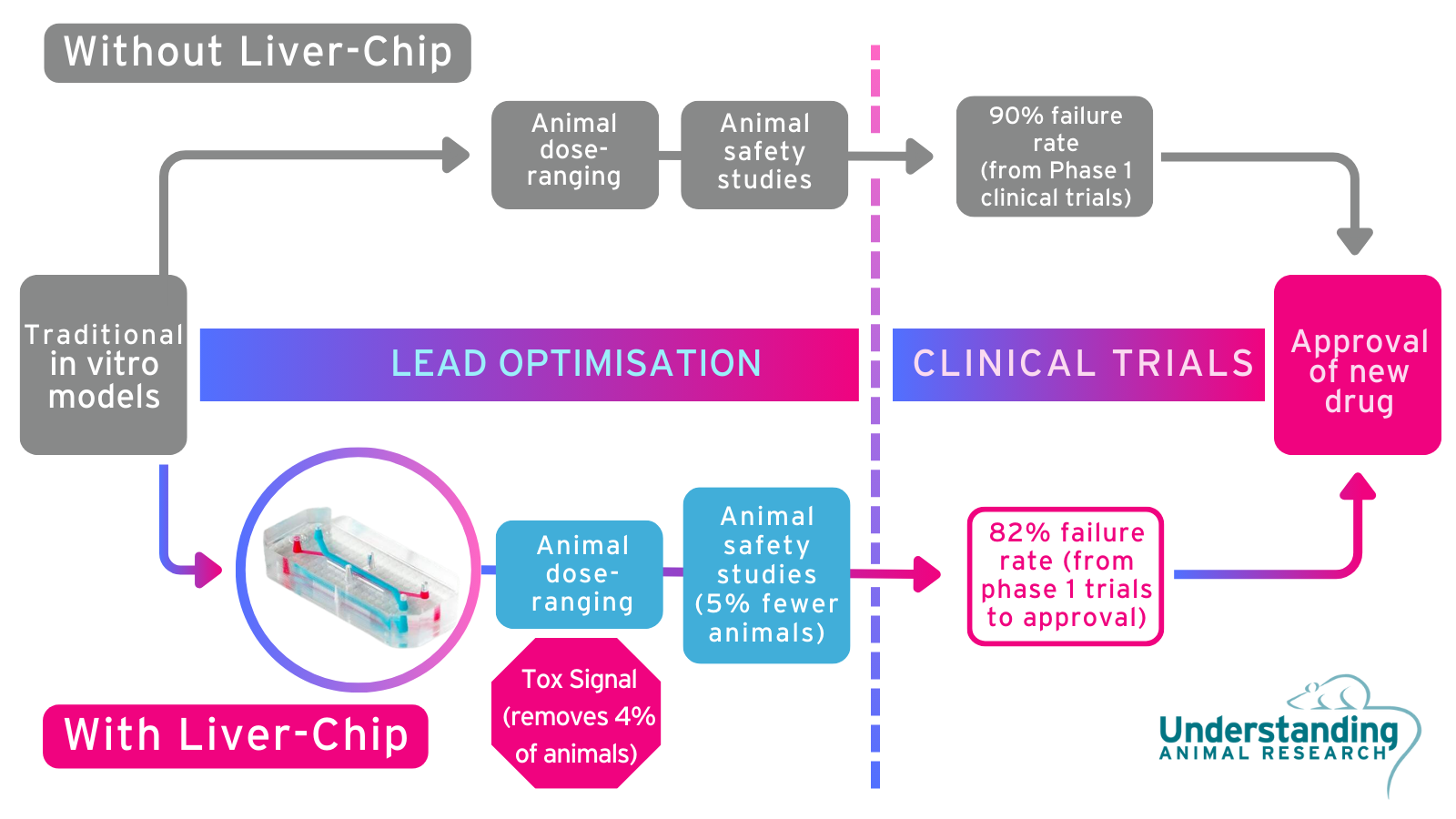

Example: Liver-on-a-chip

Drug regulators wish to know if a potential medicine is safe enough to try in human volunteers. Animals predict this level of safety very well with an 86% average prediction rate, and can predict toxicity, but cannot predict whether something will later prove to have unmanageable toxicity.

Liver chips can answer this question, at least for the liver, with 87% accuracy. Proven to be effective in late 2022, if used early in the drug development process, it can identify the 9 out of every 100 drugs that would later fail for liver-related safety issues. Understanding Animal Research thus recommends that they are used at the earliest opportunity.

Roughly the size of an AA battery, liver chips are made from a flexible, translucent polymer. Inside are tiny tubes, each less than a millimetre in diameter, lined with living cells taken from a particular human or animal organ. These are suitable for answering some simple scientific and regulatory questions and can thus reduce animal use for that purpose.