Fear is a primal emotion that has shaped the evolution of our species. It helps us avoid danger, and ultimately keeps us alive. Our brains have evolved to adapt our response to fear according to different levels of threat. But unbalanced or overactivated, this essential survival mechanism can lead to anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD). With funding from his newly received Wellcome Discovery Award, Professor Tiago Branco at University College London's Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, wishes to investigate how genetics and experience combine to help the brain set its sensitivity to threat.

Three times a year, the Wellcome Discovery Award scheme provides funding for established researchers who want to pursue bold and creative research ideas that have the potential to improve human life, health, and wellbeing. This year the funding went to Professor Tiago Branco to support a seven-year research programme on mice to understand how neurons in the brain respond to fear in order to compute the best adaptive behaviours to promote survival. How does the brain decide what level of threat requires our attention, and what happens when that system goes wrong?

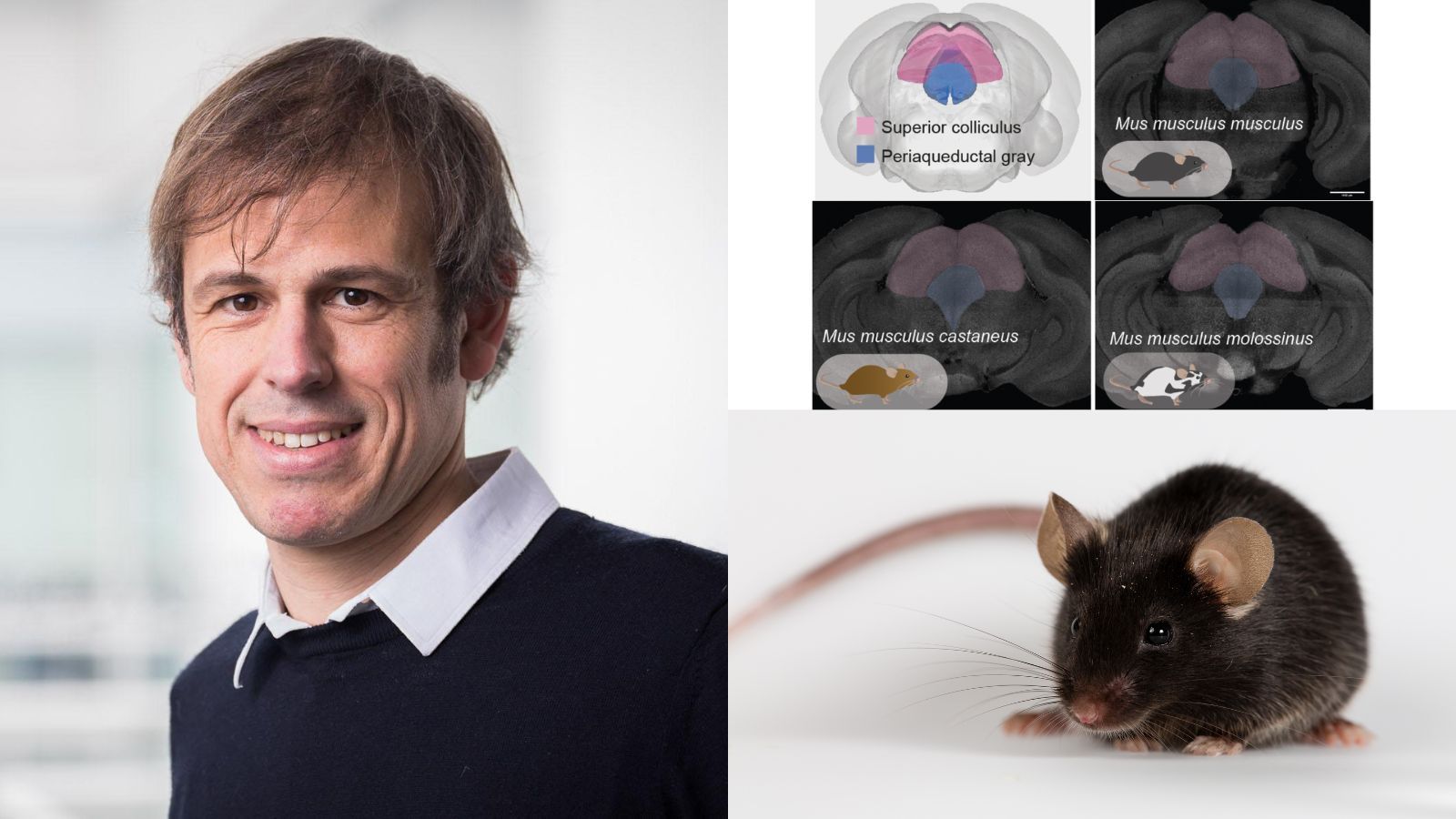

To answer these questions, the researchers will be studying different species of mice. The small rodents share remarkable similarities with humans in their brain circuitry for processing fear and making escape decisions. Just like humans, when faced with a potential predator, they must make a lot of rapid calculations: What is the threat level? Should they try to escape? What is a safe place and how can they get there?Prof Branco wants to understand the biological processes underpinning this cascade. What makes his approach particularly innovative is his focus on different breeds of mice with varying levels of tolerance to human presence. The common house mouse, Mus musculus musculus, evolved to live alongside humans, while the Asian mouse Mus musculus castaneus remained largely wild with very little human interaction. In the middle, so to speak, there is the Japanese house mouse Mus musculus molossinus which is generally considered to be hybrid of the other two with characteristics of both. The different evolutionary histories of the three mouse types led to significant variation in threat sensitivity, with some being naturally more anxious and quick to flee than others. This diversity creates a natural laboratory for understanding how genetics influence fear responses. The researchers hope to uncover the genes linked to changes in the brain that impact sensitivity to threat.

“I’m very excited that this award will enable us to do comparative neuroscience. We are going to compare different species of mice by recording brain activity, studying brain anatomy and looking at their genes. We hope this will allow us to identify genetic components to threat sensitivity that may also be present in humans,” Prof Branco told the Sainsbury wellcome centre.

Prof Branco’s lab will be primarily focussing on defensive behaviours, such as escape responses, which are innate and therefore encoded into the genome. But to do so, the researchers need to ensure that the mice experience the same environment. They will be using the cutting-edge technology developed for the Aeon platform, a new open-source system developed at Sainsbury Wellcome centre to measure brain activity and behaviours in a naturalistic environment and time frame.

The team hopes that understanding the mechanisms behind threat sensitivity will result in ways to modulate threat sensitivity up and down. This research could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets for conditions such as anxiety and PTSD, which currently have limited treatment options that mostly focus on serotonin and don’t address the root causes of inappropriate threat responses. By understanding the fundamental mechanisms that control threat sensitivity, researchers could develop entirely new classes of treatments.

Last edited: 7 October 2025 12:50