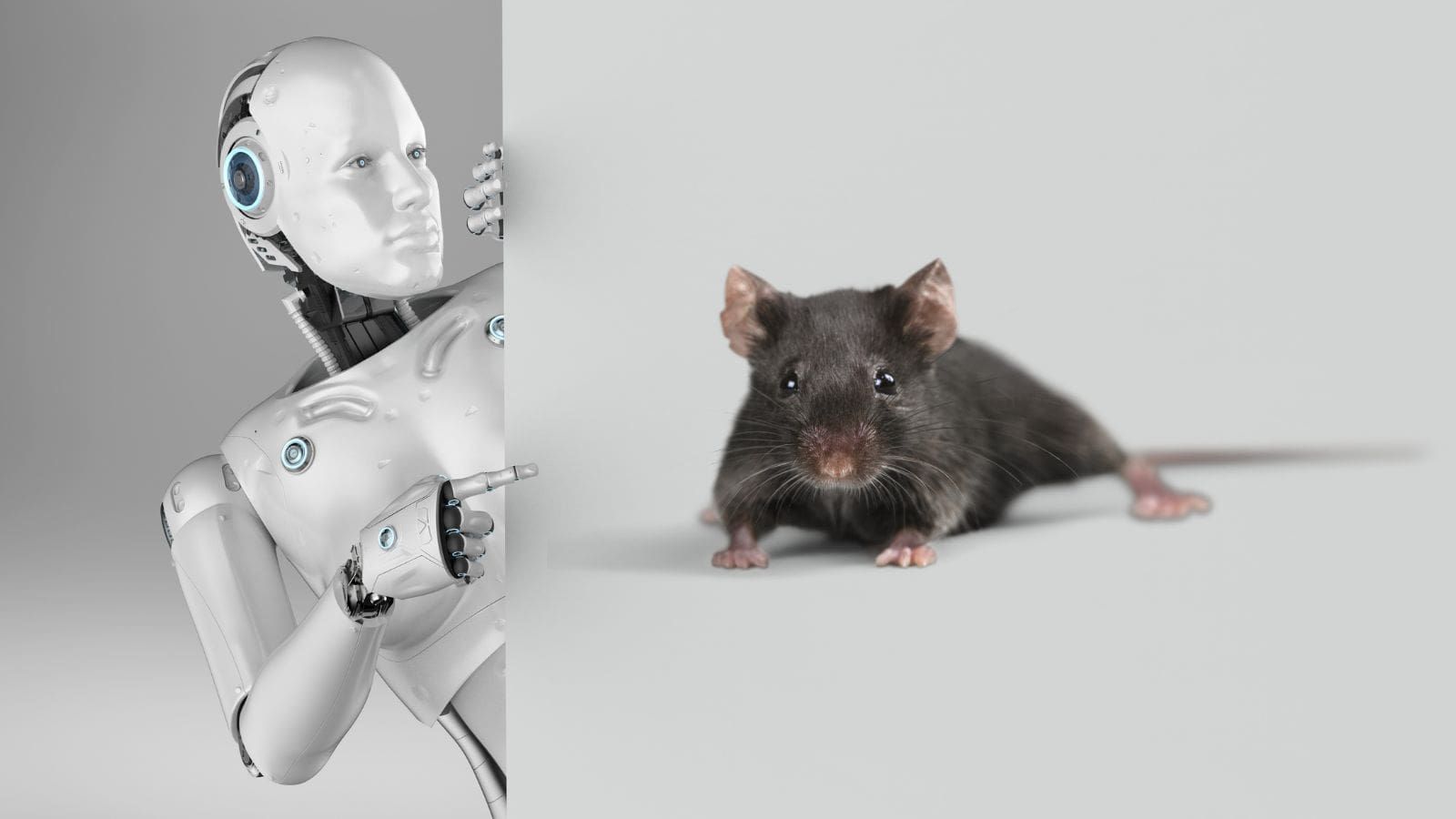

Extraordinary recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have led some scientists to believe that computer-generated models could soon replace the use of animals in the biosciences. But is it true?

On the face of it, the evidence seems compelling. Already, we are seeing the potential for AI to enhance the translation and reproducibility of animal studies, complementing the use of animal models. By analysing complex datasets, improving experimental design, and predicting outcomes, AI has already optimised and potentialized preclinical in vivo studies.

This is particularly true for the toxicology sector. In the past few years, toxicology has gone from an observational science to a data-rich discipline ripe for AI integration. While animal tests are still the mainstay to test drugs and vaccines, researchers have used AI technologies to develop computational models that replicate the behaviour of human organs, tissues and biological systems, enabling them to provide predictions of human responses to substances.

These computational models are improving the reliability of testing for toxicity, efficacy, and other relevant endpoints. Several promising tools in this line have been developed that may be beginning to reduce reliance on animal testing. These advances are likely to receive a boost from the recent decision by the FDA in the United States (the FDA Modernizing Act) to accept data from new modern methods (such as computer models, engineered organs, and organs on chips) in regulatory testing, not just for medicines but for chemical hazard assessment, to better protect human health and the environment. AI holds the promise of transforming the toxicology sector, perhaps signalling a slow turning of the tide in the use of animal models.

More commonly, however, AI technology is being used to supplement and improve the use of animals, rather than as a replacement.

AI and deep learning solutions can be used to automate the tracking and analysis of animal movements and to monitor health indicators, providing data on behavioural patterns, social interactions, daily habits, responses to environmental changes and well-being. These technologies improve efficiency and accuracy of data collection compared to human observers which, in turn, helps reduce variability in results and enhance the reliability and reproducibility of findings. Because more meaningful information can be extracted from the same animal experiments, integrated AI approaches inevitably reduces the number of animals that need to be used.

Improvements in the translation of animal data into human clinical studies have also been driven by AI. The objective of much animal testing is to act as a substitute for humans in understanding how a novel chemical affects healthy or diseased human biology. Integrating big data from both animal models and human studies using AI and machine learning has allowed researchers to identify commonalities and differences across species. These integrated approaches are helping to bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical studies, finding the points of similarity and increasing the relevance of animal model findings to human disease.

However, although AI simulations have the potential to mimic biological systems with uncanny precision, replicating cell, tissue, and organ behaviour, but they still can’t replace the real thing. Datasets that include clinical, genetic, neurological, and biochemical information from both animals and humans, when interrogated by AI, contain immense potential for transformative discoveries. But for the time being, they remain incomplete and are likely to present new and important ethical challenges that also need to be considered. The extraordinary complexity of living organisms remains a barrier even to the enormous power of modern computing.

For now, it seems most likely that the near future will see a greater application of AI as a tool to improve and refine animal research rather than a means to replace it. But artificial Intelligence is advancing at such a rate that it is impossible really to predict how big an impact it will eventually have on the biosciences and the use of animals in them. In the meantime, animal models look set to remain an essential part of medical discovery for the foreseeable future. AI promises to change the world, but not – yet – to bring an end to animal research.

Last edited: 5 September 2024 12:52