Following a report into the use of the forced swim test published by the Animals in Science Committee (ASC) in 2023, the government has accepted that the test is an effective way to screen for antidepressant medications and that it cannot currently be replaced by any other non-animal approach.

This is a significant development because the forced swim test has been the focus of a concerted campaign by animal rights groups in recent years that has aimed to have it banned on the grounds of ineffectiveness as well as alleged cruelty.

The government’s response to the ASC report came in the form of a letter from Lord Sharpe of Epsom, the minister responsible for the regulation of animals in science in Great Britain. Lord Sharpe accepted all of the recommendations in the report but went a step further, making it an aim of the government to remove the need for the forced swim test through investment to establish alternative methods leading, ultimately, to a ban.

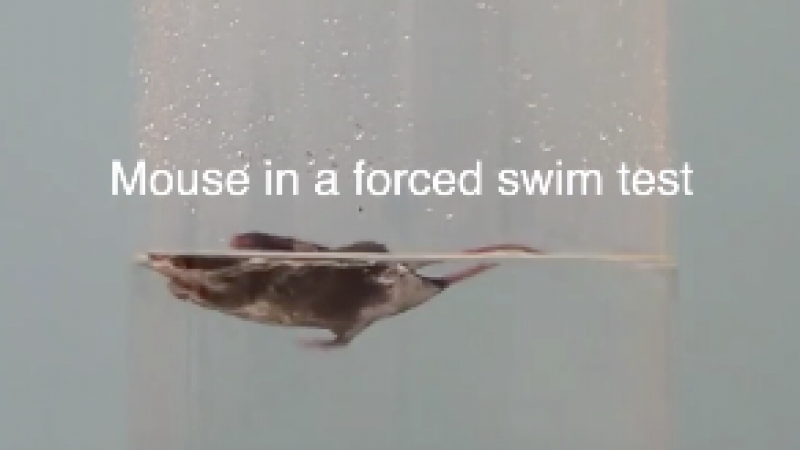

The forced swim test, which is often abbreviated to FST and is sometimes known as the Porsolt swim test, has long been the focus of controversy because it is an aversive test, which means that it exposes animals to stressful situations that they would not choose to enter themselves. The test animal, usually a mouse or rat, is placed for a short time in a container of warm water that is too deep for it to touch the bottom and from which it has no means of escape. In most cases, the test lasts for a maximum of about six minutes, during which time the researchers observe the animal to see how long it continues to swim and try to escape rather than giving up and floating in the water. No animal is allowed to drown or to swim to the point of exhaustion. If observers think at any time that the animal is at risk of drowning it is immediately removed from the water. At the end of the test, the animal is lifted out, dried and warmed and returned to its cage.

The idea behind the test is that animals treated with an effective antidepressant will swim for longer than those without. This helps scientists identify compounds that are likely to have an antidepressant effect in humans. As the report from the ASC demonstrates, the test works: all currently available antidepressants that are clinically effective in humans also induce longer swim times in animals.

There is no doubt that forcing an animal to swim without means of escape creates stress. In fact, the swim test is also sometimes used to study the physiological and neurological effects of stress. But the level of stress is relatively low, estimated to be at roughly the same level as exposure to temperatures of about 4 degrees C and, in his letter, Lord Sharpe announced the introduction of enhanced scrutiny of licensing applications yo ensure that stress is kept within these reasonable limits. This new regime includes a ban on using the test as a model for depression (as opposed to a way of testing the effectiveness of antidepressants).

The recommendations that are being implemented following Lord Sharpe’s response will also standardise the protocols for how the forced swim test is conducted (ensuring optimal conditions for different species in factors such as water temperature, for example), require higher standards of communication about the test in non-technical summaries, and make sure that project licence applications provide specific and detailed scientific justification for using it. It may be that these measures lead to a reduction in the number of animals used in the test, but the ASC found that the FST is not currently used very often, so there may not be a significant change in overall animal use.

All of this is good news for science and for animal welfare. It may be better news in the near future because Lorde Sharpe has written to the Minister for Science, Research and Innovation at the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) and the Chief Executive of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) to ask them to think about how new non-animal methods could be developed that would be effective and robust enough to allow government to eliminate the forced swim test altogether, an outcome that would be warmly welcomed by the life-sciences sector as a whole.

Last edited: 3 April 2024 15:37