Women influencing the animal research sector

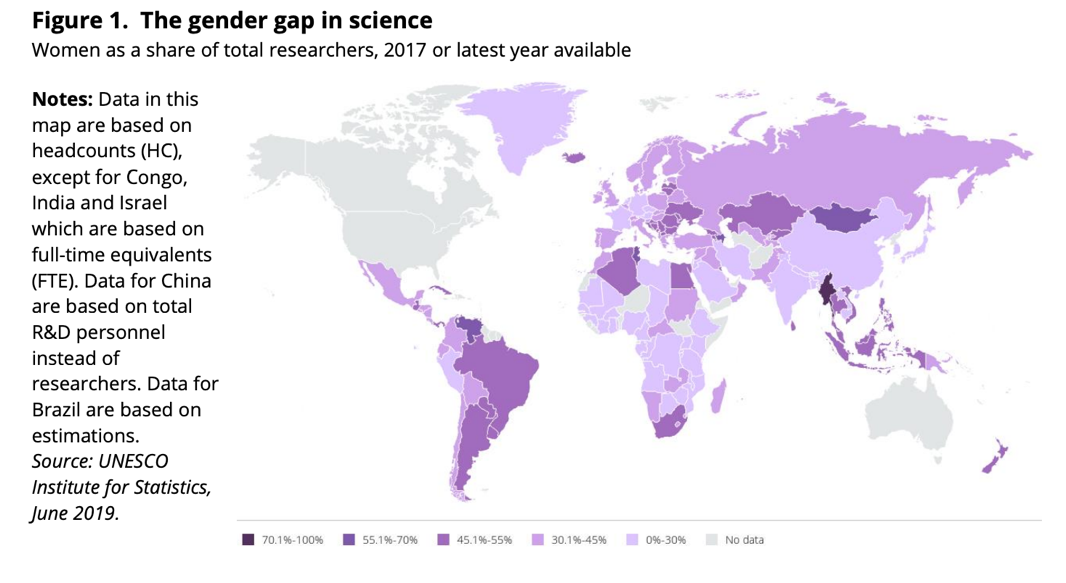

More than 100 years ago Briton Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923) wrote: “Being a scientist involves being good or not good, not being a man or a woman.” Those words echo in all women leading ground-breaking research across the world today. Still, women represent just 33.3% of researchers globally. Despite their remarkable discoveries, women have been and are still underrepresented in science. Their work rarely gains the recognition it deserves with less than 4% of Nobel Prizes for science awarded to women.

Giving a voice to senior directors in science who are women

As women embark on a scientific career, the gender gap only widens. They are often faced with the impenetrable glass ceiling of vertical segregation, encountered in almost every sector. UAR spoke to three women whose work influences the use of animals in research in the UK

and beyond.

Dr Sara Wells is Director of the Mary Lyon Centre at MRC Harwell, the UK’s national facility for mouse genetics and the use of mouse models for the study of human disease.

Dr Penny Hawkins is Head of the Animals in Science Department at the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), which provides the scientific basis that helps enable the Society to advance animal welfare effectively and work to refine animal care, reduce suffering, and improve welfare.

Dr Vicky Robinson is Chief Executive at the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement, and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs), an organisation dedicated to helping the research community worldwide to identify, develop and use the 3Rs.

“There are a lot of women in science support but fewer, higher up in the research council. Especially on a campus such as Harwell, which is heavy in physical sciences, senior directors are less likely to be women.” describes Dr Wells.

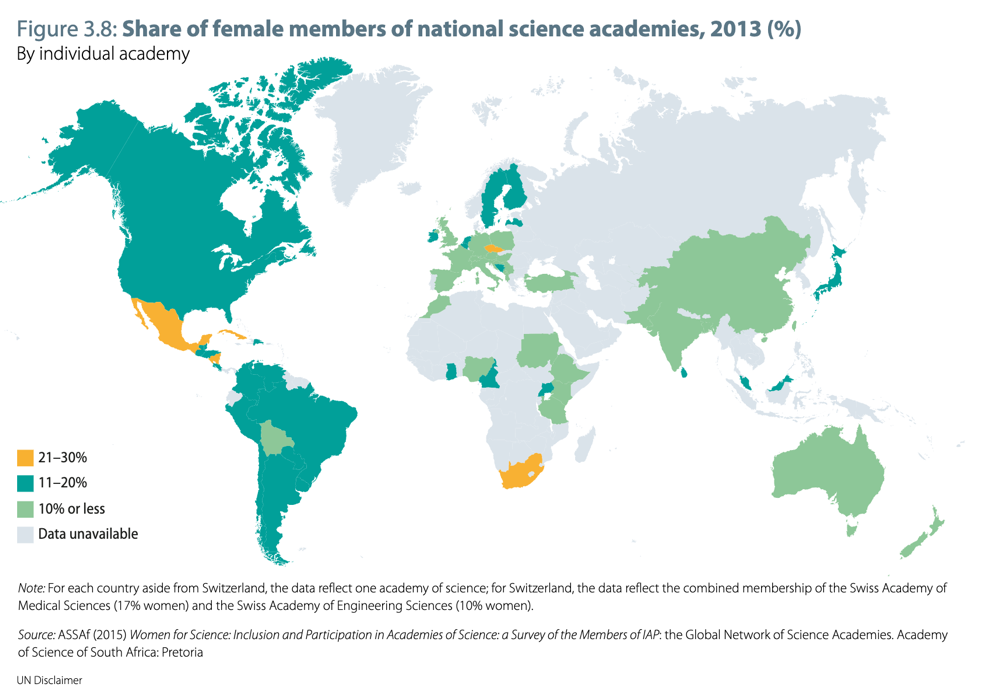

The presence of women becomes increasingly rare as they reach the higher echelons of research governance structures, such as academies of science or science councils. Although women account for four out of ten academics worldwide, only 11% of senior research roles are held by women in Europe.

“In the 1990s when I was doing my PhD, I often noticed that all the men would be introduced as Doctor so-and-so, but the women would be introduced by first names only, or as the wives of,” depicts Dr Hawkins. “And you used to have to say: Excuse me, can I have my PhD back please? I'm sure I worked just as hard for it as the men did.”

Dr Hawkins adds: “I can remember answering questions in meetings that nobody would seem to hear until a man said the same thing. These things say a lot about the viewpoints, mentalities and establishment culture, and were just completely taken for granted. If you pushed back against them, you'd be viewed as being hysterical, some sort of troublemaker with a chip on your shoulder.”

Dr Robinson describes a similar environment: “I went to many events where I could count the number of women on my hand. The thing that stands out though is the number of personal comments I used to get that I am sure a man would have never gotten. At one event I was asked if I was somebody's wife because I couldn't have been there in my own capacity. At the time it felt “normal” and who would I have complained to? It's only when I look back that I think, wow, that should not have happened.”

Women tend to be held to a tougher standard

Career prospects for women in science still remain quite daunting. They generally have to prove themselves even more in order to be heard. Studies have shown that women are often underestimated, even though they show greater and faster rates of improvement throughout their careers, in terms of writing standards and contributions to research (Brower and James, 2020; Hengel, 2017).

Dr Robinson describes: “I didn’t notice these differences then, but looking back, there were times where people would address my male colleagues because the head of the NC3Rs couldn’t possibly be me. At the press conference announcing the creation of the NC3Rs I was in the audience and not part of the panel – it was all male – despite the fact I was going to be the Chief Executive of the organisation. It wasn’t deliberate bias I am sure of that, it’s just the importance of gender balance wasn’t a consideration back then, almost 20 years ago, as it is now”

Fortunately, this gender bias doesn’t always apply, as Dr Wells explains:

“I don't feel that sex has been a differential in genetics. The people that I'm still in touch with from university who have stayed in science are all women. I think the career path that I've been in has been fairly unbiased. I've always had quite inspirational women around me that I’ve looked up to. I don't feel that my sex has ever been an advantage or a disadvantage in what I've done.”

However, still today, numbers show that women are held to tougher standards for funding applications, peer review, tenure review and job applications (Brower and James, 2020; Witteman et al., 2019; Kaatz et al.,2016; Hengel, 2017).

“I don’t think ultimately being a woman stopped me from doing anything professionally. People weren't necessarily doubting my professional ability but making more personal comments that perhaps wouldn’t have been directed at a man” reflects Dr Robinson. “Things could feel uncomfortable, but I was very lucky that I had managed to make strong connections and networks both when I was a bench scientist, and when I worked at the MRC and the NC3Rs. I felt well protected as a result. On the whole, I don’t think there were barriers that prevented my work because of my sex. The main hurdle really has been attitudes to the 3Rs and tackling that. “

Advocating for animals as a woman

Does advocating for animals as a women raise unique challenges? Dr Robinson did not think so:

“Most of the time, I didn’t have time to think about people’s attitude to my gender. I was so driven by my passion for animal welfare and obtaining a balance between science and animals. I wanted to make sure that the NC3Rs had a credible voice that could benefit the research community, in the very polarised animal research debate. That was much more challenging for me. And I don’t think being a woman threatened the credibility of the organisation.”

However, Dr Hawkins thought it did:

“Being an advocate for animals, you can find yourself being isolated for your point of view in a male dominated working group already. You can clash with people, not necessarily because they're male and you are female, but because you are holding different viewpoints and advocating for different interests. But as long as I am confident in the evidence I hold, I don’t get intimidated, hold my ground and don’t let people talk over me, skills that often come with age and experience.”

Dr Hawkins continues: “That says more about the person I am than my sex. I was brought up in a household that recognised that men and women are equals. I remember my dad telling me, that I could do anything I wanted to do, always supporting me, and never trying to force any gendered roles onto me. I still have that support from the people around me today. I think the important thing is really to listen to yourself and believe in yourself.”

Caring for animals

For all three women, working with animals has always been a huge part of their careers. In Dr Robinson's own words:

“Animals are really important, and it is a responsibility and a privilege to be able to use them in research. It is important not to forget that. Researchers need to take that seriously and to do the best they can for the animals in the context of their work.”

Dr Hawkins explains that it is important to recontextualise the anthropo-centric feeling of what it means to appreciate animals, to understand who might fight for their rights.

“Lots of people might describe themselves as animal lovers, and love their pets, but don’t think too much about what it is to love all the other animals that live in this world. Instead of describing myself as an animal lover, I say that I respect animals. I believe that they can suffer and are often caused to suffer unavoidably by humans prioritising their interests unfairly over those of other animals. I feel strongly about injustices, which brings me to fight for the injustices that animals go through. I don’t have data, but I can imagine women being particularly motivated to think about other disadvantaged groups and ways to help them.”

Dr Hawkins adds: “However, from my own personal point of view, I tend to push back against this natural idea that women should be carers. I think that that leads to a lot of caring work getting ‘dumped’ on us, that other people don't want to do. I prefer to think more as women championing the vulnerable and pushing back against injustice.”

What is more, caring for animals isn’t necessarily a female-driven field. For Dr Wells:

“There are certain people who share more empathy than others with animals, but I don't think that's necessarily based on their sex or gender.”

The field of animal welfare is not only filled with people whose primary role is one of caretaking. Scientists and statisticians, among others, play a big role in setting standards for animal welfare.

Dr Robinson explains: “The animal welfare sector might have been led predominantly by women in the past, but I think this is shifting because it isn’t just about the animals, it’s also about doing robust science. There is a wide spectrum of people that contribute to animal welfare, from those who are driven by animal welfare to those interested in the science and technology development. From my perspective it doesn’t really matter as long as the outcome is the same.”

The heavy weight of children

For Dr Wells, one of the major hurdles in her work is having children late in life. Most senior members in the workplace don’t have young children and little is done to work around that, she explains:

“I had children quite late, which was partly because my career was developing, and it wasn't the right time for me. Today I’m faced with long working hours and heavy meetings being scheduled during half term or on the weekend, which can really be challenging. I think that's the biggest challenge: being a mum, not necessarily being a woman. Being a woman – or a man - with children is not always taken into consideration once you get to a senior level.”

And indeed, it has been shown that women are as productive as men in terms of research output but tend to have shorter careers, with greater rates of departure at each stage of their career (Huang et al., 2020). The difficulty in balancing work and family has been documented as one reason why women cut short their research careers.

Things are getting better for women

Since the 2000s, the European Union has supported the principles of parity and equality in careers and professions. Dr Hawkins describes:

“Things seem better in work situations now, but I don’t know whether that's just because I've got older, more confident and better at asserting myself, and things may be as bad as they always were. Certainly, the number of female inspectors and managers have increased a lot within the RSPCA. I have to say that within the science departments of the RSPCA there’s always been good female representation, and the current leadership team has set up an excellent equality program.”

Dr Robinson adds: “On the whole, the field has evolved in a really positive direction, but there's still work to be done. As women, we need to continue to step up and to show the important role and contributions we make. We’ve gained a momentum, but we do need to keep driving that trajectory, raising visibility, supporting other women and encouraging them to apply to jobs in the sector.”

Dr Robinson continues: “Actually, it's not just about supporting other women, it's also about supporting early career researchers too. Science can be a really competitive environment. We will only be successful if we work together and if we work together well and that can only happen if we have an inclusive culture. I always take great pride in supporting all staff at the NC3Rs, women can have many things to juggle with work and home life responsibilities, and it is important to create an environment that is supportive. I think that if you have a leadership role this is particularly important to do.”

Of course, there is still much more to be done to achieve true gender equality in science. But like the Lithuanian American astrophysicist Vera Rubin (1928-2016) wrote in her 1997 book Bright Galaxies, Dark Matter;

“there is no scientific problem that a man can solve that a woman could not”. Hopefully the scientific sector will soon reflect that reality."

Last edited: 9 February 2023 17:14