While well-intentioned with his desire to end experiments that use animals, Will Young has fallen into a fringe echo chamber and has been served a full diet of misinformation that is inspiring his actions today. He has been quoted as describing experiments as ‘heinous’ and of ‘low scientific value’ as well as repeating myths around animals leading to ‘92%’ failure rates of new medicines.

The people advising Will Young are steeped in myths, misconceptions and occasional statistical trickery. Here is a brief rundown of the main myths, which are typically an inversion of the true state of affairs.

1. The animals are mistreated

2. Animal models are most of research spending and activity

3. More than 92% of animal tested drugs fail in humans

4. ‘Species differences’ are insurmountable

5. The biosciences aren’t already working on animal replacements

6. Animal tests have never been validated

7. People are killed as a result of animal tests

Myth 1: The animals are mistreated

Tl;dr: Most research animals will be humanely killed for various reasons, but their lived experience involves very little severe suffering.

An unhealthy or unhappy animal is not much use as a test subject. Most research animals are mice, fish or birds, but some dogs are still used. Each animal is kept in a way that’s appropriate to its species. For dogs, they naturally live in a pack with other dogs, not humans, so they are kept in social groups from the breeder all the way through to the lab.

Lab animals are under the permanent care of a vet and a team of specialist animal technicians and live in a climate-controlled environment with all the water and food, bedding, enrichment and exercise they need.

There are certain practical elements to keeping dogs which means that breeding facilities look much like animal shelters. This picture is from inside the MBR Acres site which has been subject to the Camp Beagle protest supported by Will Young:

Inside the lab, the setup is similar except the dogs move in and out of clinical areas as you can see in this video.

The objectives of the current system for breeding and caring for animals are to create individuals that are content to be in a lab environment, and are in great condition, free from disease with a known genealogy and health history. It would not be ethical or effective to use animals bred or conditioned for another environment, or to mistreat them. For the majority of animals, their lived experience will involve minimal suffering, with their value to science, society and medicine often realised from studying their vital signs whilst alive and bodily tissues once they have died.

There is a distinction made between an animal’s loss of life and their experiences while alive. The ethics of each experiment is considered in terms of likely suffering balanced against the potential benefits in terms of animal and human health: the suffering the experiment may prevent. At its simplest, this may be something like studying fish to understand how they are affected by drugs such as cocaine or human hormones such as oestrogen which enter rivers and streams when people pass them in their urine. At its most complex, the benefits may only be realised long afterwards, such as when experiments using mice ultimately led to mRNA vaccines for Covid.

In terms of an animal’s lived experience, severe experiments – which can mean severe suffering, extended moderate suffering or a departure from an animal’s natural state – make up 2.6% of experiments. Experiments which involve moderate suffering such as surgery followed by recovery make up 15.5% of experiments. Some 81.9% of experiments are mild, the sort of thing pets routinely experience at the family vet such as an injection, a blood test or a procedure even milder than that.

Severity data from www.gov.uk

Myth 2: Animal models are most of research spending and activity

Tl;dr: Non-animal methods already receive most research spending.

The MRC calculates that only around 30% of active MRC-funded research grants involve the use of animals. This doesn’t mean these studies only use animals, but animals are part of the mix of techniques. The other 70% do not use animals at all. For charities, grants that use animals as part of the work make up just 20% of spending. Non-animal methods are also usually about four times cheaper than animal models. The point about animals in research is that, while they receive a minority of funding, the insights they provide are particularly useful: animal experiments can’t be done in any other way (if there is an alternative the law requires it is used) and to fail to do the animal work would lead to worse ethical outcomes.

Myth 3: More than 92% of animal tested drugs fail in humans

Tl;dr: Lots of drugs (around 86%) fail to get from the lab bench to market, but it doesn’t have much to do with the animal model.

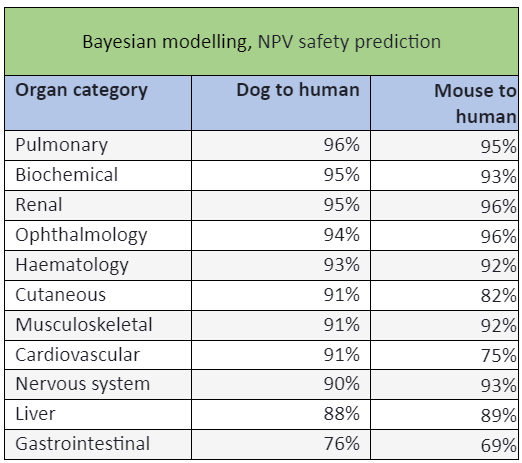

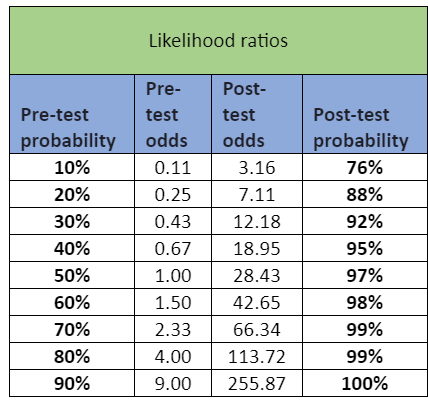

Lots of methods are used to try to find a promising drug candidate and most don’t involve animals. In vitro tests, in silico (including AI), animals, or some combination of these are used, but most won’t work for some reason. Hartung et al report that animal use in finding drug candidates has dropped by 80% since the 1970s peak. Around 10,000 candidates are whittled down to create a shortlist of around 250, then a shorter list of 10–20. If a drug developer thinks a compound has a decent chance of becoming a medicine, they then have to submit it for regulatory testing, which is a combination of human, animal and non-animal tests. Non-animal safety tests are done first, then the drug is given to two species of animal. This process removes about 40% of candidate drugs as too dangerous to proceed. Animals predict the safety of phase 1 human trial volunteers 86% of the time on average, but values for most organs, such as the heart or kidneys, are above 90% and for dogs the average is 91–92%. The state of an animal’s tissues post-mortem also gives hints as to whether a compound might need to be managed to be safe –doses of drugs such as paracetamol need to be spaced out to be safe, for example. The reasons for drug ‘failure’ thus cannot reasonably be pinned on animal tests – they were not usually the origin of the hoped-for efficacy, they predicted human safety extremely well, were crucial to the design of the human trial and cannot be blamed for the commercial failure of a product.

Further reading

Animal activists’ retort to this will be that the entire international community is using the wrong statistical model, that likelihood ratios alone should be used (so you know the specificity and the sensitivity) and that these ‘prove’ the second animal species adds no further value to the tests. This is all based on this problematic paper, which was authored by activists.

There are several issues with it. The first is, it doesn’t analyse any of its own data that disagrees with its conclusions. The second is, sensitivity and specificity are inversely proportional, meaning that as the sensitivity increases, the specificity decreases and vice versa. It’s a perfectly fine statistical model, but is better seen as adding a new dimension to the information, as you can see from the tables below. Sensitivity and specificity are also not strictly necessary for the question the regulator is asking: ‘Is this drug safe enough to proceed to human trials?’ The Bayesian statistical model the activists’ paper (baselessly) rejects does answer this question. For completeness, the following table is what you get when you compare the traditional statistical model, and include all the data in the likelihood ratios:

Date sourced from here and here.

Both show that animal models actually add quite a lot of certainty.

Myth 4: ‘Species differences’ are insurmountable

Tl;dr: If this were a dealbreaker, medicines like insulin wouldn’t have worked.

There are of course crucial differences between species. However, they are well known and characterised. Sometimes they’re critical, often they don’t matter.

Type 1 diabetics used pig or cow insulin to control their blood sugar for most of the 20th Century because it’s so close to human insulin. There are thousands of biological systems that are near identical between animal species, including humans. We have also long been able to make ‘humanised’ mice, which are bred with human traits like an immune system that reacts in a human-like manner.

On the other end of the scale, we study zebrafish because, unlike humans, they can heal without scarring. Dogs can’t eat chocolate and cats shouldn’t touch ibuprofen. The point is, we know what the differences between species are in some detail – sometimes the difference is the point of the research. This allows us to select the right animal model for the right application. The reason one might use a primate instead of a dog in drug testing, for instance, depends on what you’re testing – is it a large or small molecule? Is it a vaccine? Species are not selected randomly but because of their species’ characteristics.

In areas such as basic research, scientists will try to understand a biological process in the species they’re studying, e.g. in mice. This might be a natural, healthy process or one associated with disease. They aren’t necessarily speculating that the finding will have immediate clinical relevance for humans – maybe it will be of use in veterinary medicine or conservation – but they are attempting to find one more piece of a jigsaw that may only be fully assembled much further down the road.

Myth 5: The biosciences aren’t already working on animal replacements

Tl;dr: Non-animal techniques have been in use for years, and are often developed by those who also use animals. Non-animal techniques are typically used alongside animals in the same body of work.

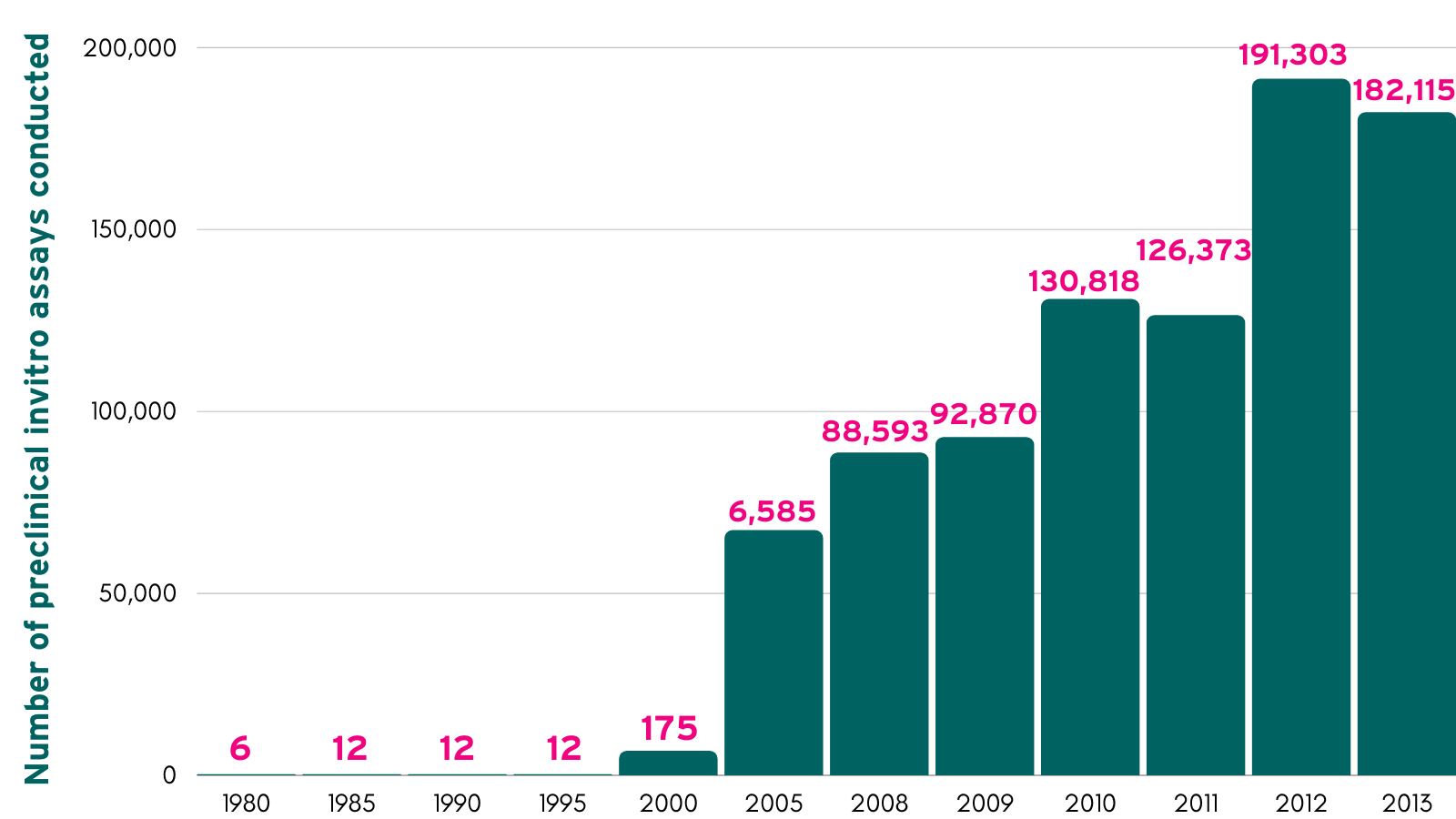

The biosciences have been working on non-animal tech for decades, using it as it becomes usable. It is already the law that animals cannot be used if a validated non-animal alternative exists, but there are other drivers such as ethics and cost which mean researchers will use non-animal methods where they work. The introduction of non-animal methods was charted in 2015 by Goh et al but has continued to rise at a growing pace as non-animal methods have improved.

Goh et al. Number of preclinical in-vitro assays conducted 1980 - 2013

In 2004, the UK established the NC3Rs, a centre for developing non-animal methods, reducing animal numbers and refining experiments to reduce or remove suffering. It plugs into international networks to effect global change. In 2009, for instance, it removed the only animal test where death was the intended outcome (ICH M3), changing the international standards for testing.

The NC3Rs is by far the best funded and most respected organisation seeking to make animal tests unnecessary, with £10million core funding, which is built upon by project funding, that eclipses the amounts spent by other countries and much smaller charities.

The NC3Rs has a project to make a ‘virtual dog’, mining the excellent predictive powers of dog data using computers. This project has a further five years to go before it is known whether, and by how many, dogs may be avoided in drug testing. The world is watching this project through international consortia like the ICH.

In reality, most programmes of work have animal and non-animal elements. It is not an either/or question.

Myth 6: Animal tests have never been validated

Tl;dr: Yes, they have. It didn’t happen the same way as New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) because NAMs don’t have 150 years of data to draw from.

Validation simply means proving that a research method works, and it comes in several forms. Animal tests are validated by sound study design, criteria first proposed in the 1960s, and looking back at decades of data, whereas new methods don’t have 150 years of information to draw from. Thus, they must prove their effectiveness through specially-commissioned tests.

In 1969, McKinney and Bunney were the first to propose criteria on the external validity of animal models, mainly focused on affective disorders. In 1984, Wilner simplified these external validations to three: predictive, face, and construct validity. These remain the most widely-accepted criteria for external animal model validation. However, internal validity (experimental design, reproducibility, randomization, control, etc.), applies to all scientific research and the precedent for using a particular animal model for a particular application is also contained in the scientific literature specific to that application, e.g. immunology.

Animal model validation tends to be for extremely specific applications. For instance, this animal model tests the safety of immunotherapy for cancer that stimulates PBMC necrosis factor receptors via the activation of the 4-1BB (CD137) costimulatory molecule. Models of every kind are not intended to be a panacea, but a very specific tool for a very specific job.

Myth 7: People are killed as a result of animal tests

Tl;dr: There has only been one death in living memory that can plausibly be attributed to the failure of animal tests, whereas tens of thousands of deaths have been prevented.

No drug is licensed on the basis of animal tests alone – any new drug will mainly have been tested on non-animal assays and humans. In UK drug testing trials there have been no deaths and only one serious incident since 1968. In that incident, in 2006, none of the participants died. The only death in living memory during phase 1 human trials was in France in 2016, where 90 volunteers were given a drug, six fell ill and one died. Just 0.3% of phase 1 clinical trials result in a serious adverse event.

Around 40% of drugs are weeded out by preclinical research as being too dangerous to try in humans. Therefore, the animal testing stage prevents thousands of human deaths each year.

Read more Mythubusting

Last edited: 9 September 2025 11:34