Human influenza (flu) is a very fickle virus. Because circulating flu viruses are constantly changing, the composition of the flu vaccines made to protect humans against them have to evolve accordingly. The current flu varieties are reviewed every year and this provides guidance to the vaccines makers – although virus evolution can outrun the production cycle so virus vaccines vary in their effectiveness.

Targeting the right virus

Every year the predominant strain of the influenza virus evolves. Changes often occur in the proteins on the surface of the virus. This affects its antigenic properties, which means that any immune protection built up by a previous encounter with the virus is often rendered useless because the body can no longer recognise the flu virus.

Scientists seek to predict these changes to create new vaccines that can protect populations at risk.

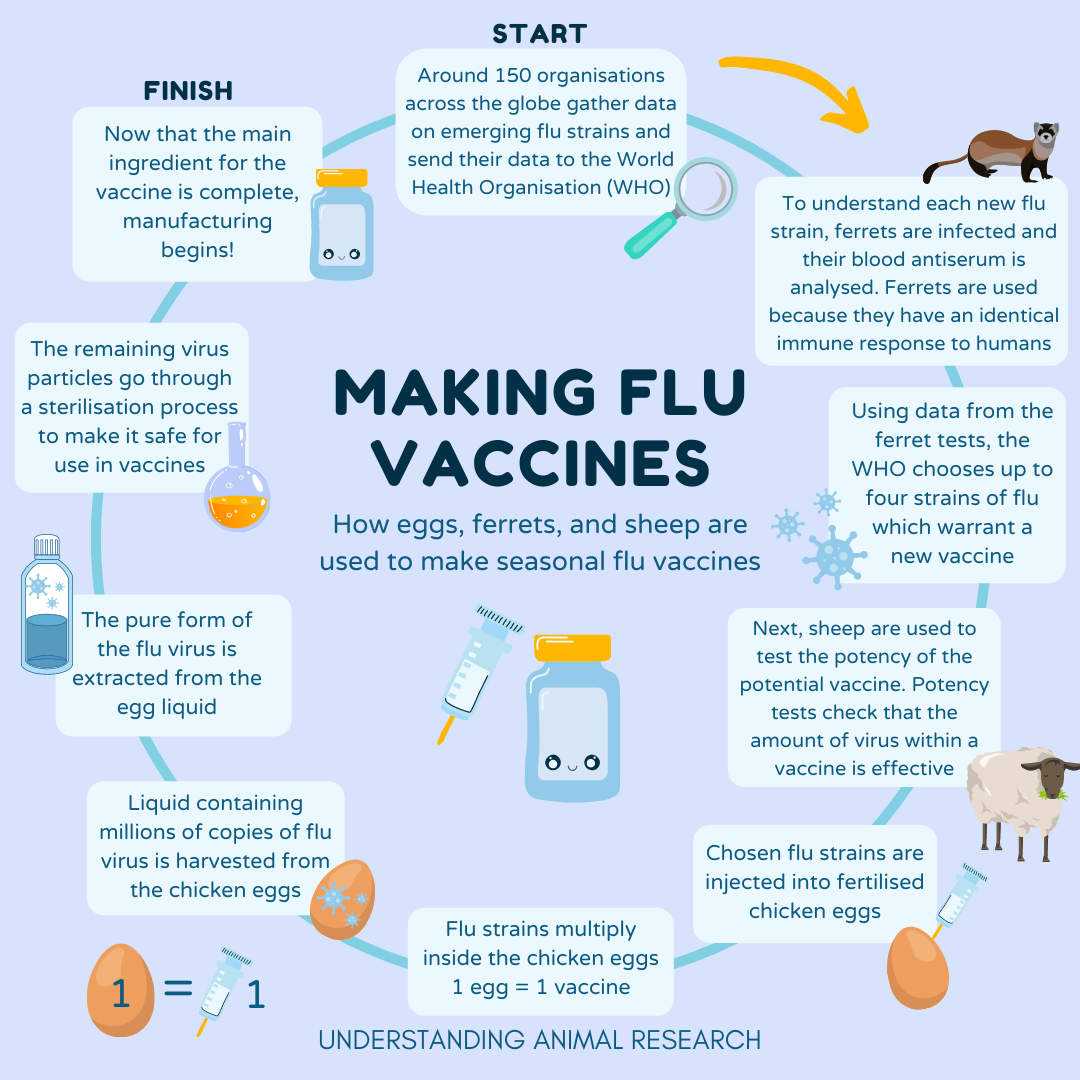

“We have a global system consisting of about 150 laboratories in 125 countries around the world monitoring their influenza viruses,” explains John McCauley, Director of the Worldwide Influenza Centre at The Francis Crick Institute. “In a global effort, the WHO network called Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System shares data and clinical samples to try to identify the next virus most likely to cause an epidemic.”

The researchers analyse the antigenic properties of circulating viruses, in particular their ability to bind to red blood cells and infect cell tissue culture. To do so they need an antiserum. It is made by taking the virus of interest and infecting a ferret with it.

“Ferrets are used because they mount a similar immune response to humans. Moreover, when the human influenza virus is inoculated into a ferret, it doesn’t need to change to replicate in it, whereas if it infects a mouse, the virus becomes mouse adapted,” explains McCauley.

After the ferret mounts an antibody response and recovers from the disease, its blood is collected. The blood contains antiserum which is used to assess the properties of the circulating virus, ie how the virus is recognised antigenically, and whether the antiserum can recognise and/or neutralise other or new variants or groups of virus variants. Determining whether the antiserum is effective or not against circulating flu viruses will help predict influenza epidemics and how the flu vaccines need to be updated.

“This happens every year, throughout the year, for different viral strains. Our laboratory uses perhaps 50 ferrets in a year for making these antiserums,” adds McCauley. “But it is a shared resource, and the global data from different WHO collaborating centers helps assess and define the best vaccine for the following season.”

This has to be done at least six months before flu season because you have to allow time for vaccine production and delivery.

Potency tests

After the viral strain is selected but before the vaccines go to production, they have to go through a series of tests to make sure the amount of viral strain used in the vaccine is effective. “The regulators have to do potency tests to make sure that the vaccine is what it says it is, in the amount that it says it is,” explains McCauley.

Sheep are inoculated with the particular viral strain of interest to develop antibodies against it that are then harvested.

“This is more like a vaccination or an immunisation. It isn’t an infection,” says McCauley.

This potent antibody serum is used to assess the quality and the quantity of the new vaccines. All human influenza vaccines have to undergo a potency test.

Production

Once the new vaccine has been shown to work, it has to be mass-produced. There are two ways of manufacturing a flu vaccine: an egg-based method; and a method that uses tissue cultures.

For the past 80 years, much of the world has relied on chicken eggs for the production of influenza vaccines. It is the most common way that flu vaccines are made. The selected viral strains are injected and grown in fertilised hen eggs.

The virus replicates in the fluid of the egg and is then harvested. The viruses are either inactivated or attenuated before they are purified and used in each and every phial of vaccine.

McCauley explains: “The eggs are embryonated (fertilised) eggs. In the UK, their use for vaccine production doesn’t fall under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act for two reasons. Firstly they are used for manufacturing - not animal scientific procedures - and therefore follow a different set of regulations. Secondly, the embryos, rarely over 14 days old, are not counted under the act. If for some reason, to improve viral replication or isolation, embryos older than 14 days are used, the UK and European laws with respect to animals used in research are applied.”

There is also a cell-based production process for flu vaccines that was approved by the FDA in 2012. Instead of using an egg, the virus is grown in mammalian (usually dog) or insect cells.

Despite being the cheaper method, the proportion of egg-based vaccines is slowly decreasing in proportion in favour of cell-based vaccines.

“Especially over the last 10 years, there has been a lot more emphasis on moving away from eggs as a production platform for a number of reasons,” comments McCauley. “When you inoculate a virus into an egg it generally does change, but it’s been recognised that you’re probably better off, at least for some subtypes, not using it. I suspect that over the next few years, cell-culture based vaccines will be favoured.”

He adds: “Ideally in the future, the whole process would be cut down. We’d like to be able to deduce more from viral genetics and predict all the antigenic properties of a virus from its gene sequence which wouldn’t use animals at all. This is how most of the coronavirus vaccines have been produced. But we’re not in a position where we can move away from having to really validate our claims or our predictions. We want to be right or as right as you can be. So the work we do is still important in the whole production process.”

Last edited: 14 March 2022 15:02