Not many people can say that they have made a difference in their field, but John Waters is one of these people. Chief Animal Technician at the University of Liverpool for over 30 years, in 2020 he won the Outstanding Technician of the Year award at the Times Higher Education (THE) Awards. The THE Awards are widely recognised as the ‘Oscars of the higher education sector’. We talked to John about his life-long passion and commitment to instilling a culture of care at the University of Liverpool and improving animal welfare standards across the UK.

Like most animal lovers, John Waters started off wanting to be a vet. However, coming from quite a modest background, being supported though vet school would have been quite difficult, so he turned to other careers involving animal care. He contacted the Institute of Animal Technology (IAT) asking for information about animal technicians.

“I was put in contact with the facility manager of Liverpool University and was invited to look around. Fortunately, there was an opening position for a trainee technician. I stayed at the University of Liverpool for 30 years, working in the medical school, School of Tropical Medicine, and eventually in animal behaviour and welfare at Leehurst, which is the university’s vet school,” John tells us. “I don’t regret one minute not becoming a vet and choosing to be an animal technician”.

He adds: “I think being an animal technician is a fantastic rewarding career, especially if you love animals. We are involved in helping for a better tomorrow, and improving the welfare of the animals involved. Animal technicians are a vital part of the culture of care. These are some of the most dedicated people I know. It is not a job that you can switch on and off. If you love animals, then it is absolutely a career for you.”

In his words, you can’t not love animals and become an animal technician. Animal technicians devote their whole career to looking after animals within research.

“I think most - if not all - technicians wouldn’t use animals in research if that was an option. Unfortunately, in the current state of things, there are no alternatives to using animals in research. I devoted my career to giving those animals the best life they could possibly have. I put my heart and soul into looking after these animals, and pushing for positive welfare improvements.”

Throughout John’s career, the care of animals in laboratories has improved for the better.

“In the 90s, cages were quite barren. Nowadays it is frowned upon not to provide minimal enrichments for the animals. It means you are missing out on the culture of care,” stresses John.

It is an animal technician’s duty to keep up to date with all the new policies and best practices that surround animal care.

“As an animal technician your training is your whole career. I don’t think you ever stop learning,” adds John. “As you learn, you get more confident in your role, and you start to get a bit more of an insight into the different species you care for and how to improve their welfare. Experience allows you to make adjustments that benefit the animals.”

The role of an animal technician is to understand each and every species that are cared for and provide them with the best possible welfare. This sometimes means, pushing for new ways to care for the animals. John told UAR:

“I think the best ideas come from the people who look after the animals, which is best exemplified by the Andrew Blake Tribute Award . They are the ones who know the animals the best and see how the animals respond.”

He adds: “I think it’s vitally important that the animal technicians are included in the reflection. No one knows their animals better than the animal technicians themselves. Researchers are often quite open to having two-way conversations about improvements because animal techs are their eyes and ears when they are not there.”

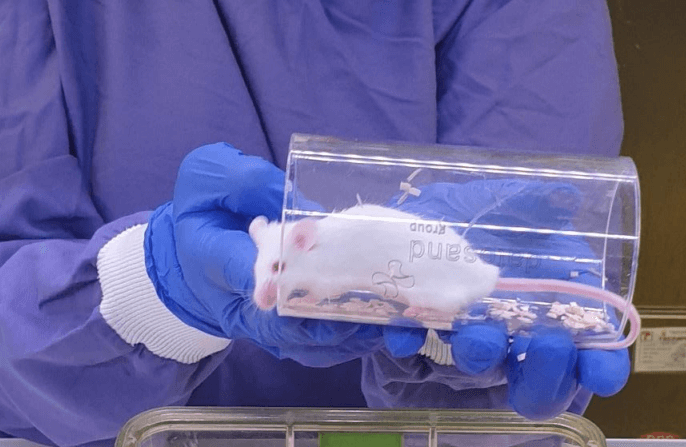

This is how John took part in the development of tube-handling and cupping as new methods for replacing the tail-handling method of moving mice that was routinely used in labs across the world. Picking up mice by the tail has been shown to cause the animals stress. Now more humane handling methods that reduce stress and anxiety in the animals are being shared widely, in part thanks to workshops and training courses that used to be run by John in the UK and internationally.

This is how John took part in the development of tube-handling and cupping as new methods for replacing the tail-handling method of moving mice that was routinely used in labs across the world. Picking up mice by the tail has been shown to cause the animals stress. Now more humane handling methods that reduce stress and anxiety in the animals are being shared widely, in part thanks to workshops and training courses that used to be run by John in the UK and internationally.

“Early on, I saw that the animals responded much better to the handler if they were not picked up by the tail. From an animal technician’s point of view that gave me a better sense of job satisfaction. I was doing something that the animals preferred and were responding positively to,” John explains.

John’s passion, practical insight and support for other animal care staff have been key in achieving widespread uptake of better mouse handling techniques across the technician community. This enormous commitment and leadership in improving the lives of laboratory animals, and the people who look after them, was commemorated in the field when John was named the Technician of the Year for his role in improving and supporting animal welfare standards.

Today, John works for Castium, a company that provides decontamination services to the lab animal sciences sector.

“I wanted to stay involved in the animal industry and continue helping as much as I possibly can. Having shifted to the trade side, I still have the insight and the ability to make a difference to animals.”

Throughout his career, John went above and beyond to improve the lives of laboratory animals – locally, nationally and internationally – and the people that look after them. He has made a real difference to laboratory animal care.

Dr Jasmine Clark, Newcastle University, demonstrates tunnel handling as the preferred method of picking rodents up in the laboratory.

Last edited: 8 March 2023 16:22