Animal models of long Covid

The COVID-19 pandemic may have passed, be we are left with pressing questions about the SARS-CoV-2 virus that conquered the world and especially about the long-term consequences of the infection. Not everyone who develops COVID-19 recovers completely after a couple of weeks. Some report symptoms even years after infection. To try to understand the post-COVID-19 condition, researchers have developed a number of animal models.

What is long Covid?

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 primarily attacks respiratory epithelial cells and induces a wide variety of symptoms, including fever, cough, fatigue, headache, dyspnoea (shortness of breath), loss of taste and smell, and neurological complications. For most patients, the infection resolves in a matter of days. However, about 30-75% of patients who have had COVID-19 in the past three years have experienced symptoms months after clinical recovery after the infection had cleared.

This condition became known by the unofficial term “long Covid” but is referred to by many clinicians today by other terms such as “post-Covid-19 condition (PCC)”. The most common symptoms include fatigue, dyspnoea, arthralgia, myalgia, cardiac complications, and memory problems. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defines the condition as long Covid when Covid symptoms persist, re-establish, or first appear more than four weeks after initial infection, although other bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) have slightly different criteria.

It should be noted that some researchers have rejected the identification of long Covid as a distinct condition. A recent study led by Dr John Gerrard, Chief Health Officer for Queensland Australia, found no difference in long-term impairment post-Covid than for other viral infections such as influenza. This does not imply that the experiences of long Covid sufferers are not ‘real’ but only that they might be better conceptualised as part of a broader study of post-viral impairment, an idea that does not invalidate any ongoing research into long Covid.

However long Covid is understood, as a unique condition or one expression of a broader viral effect, it can severely impact quality of life. It has been hypothesised that prolonged inflammation, viral persistence, and virus-induced autoimmune reactions could be the cause of symptoms but, unfortunately, the condition has yet to be characterised at the molecular level, which makes the development of targeted treatments more challenging.

Why animal models?

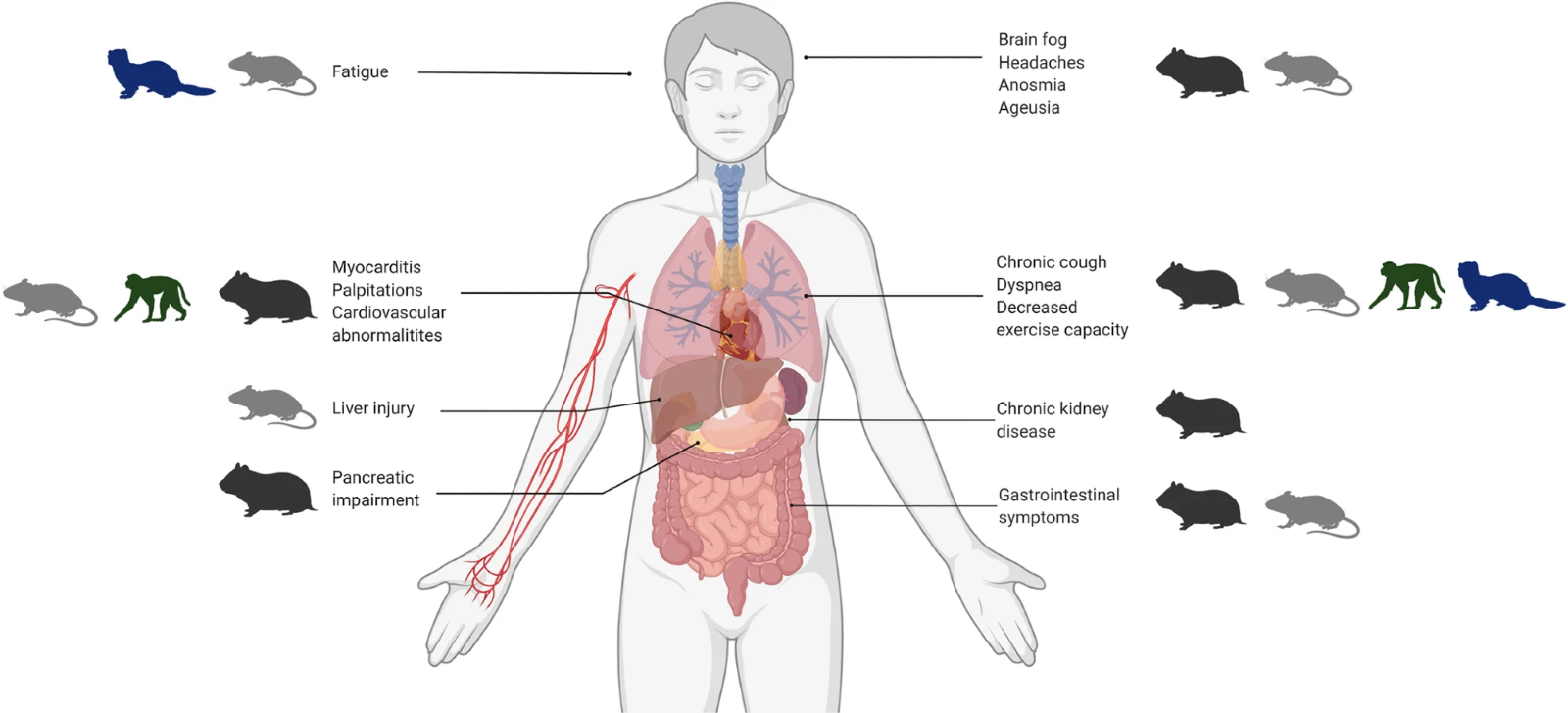

In pursuit of a better understanding of the causes of and, therefore, potential treatments for long Covid, animal models are essential. The use of animal models enables the study of disease in a complete biological system which is extremely important when researching viral effects that manifest in complex, multi-system patterns across an organism. Several animal models, including mice, hamsters, ferrets, and monkeys were used during the pandemic to study SARS-CoV-2 transmission, infection dynamics and therapeutic interventions. Many of the same models are contributing to a better understanding of the long-term repercussions of the virus. As in most diseases, no one animal model seems to fully reproduce long Covid as it occurs in humans, but several studies conducted on different species have yielded interesting results.

The four main groups of animal models (hamsters, mice, ferrets, and NHPs) are outlined with corresponding human manifestations of PASC.

Ethan B. Jansen, et all. After the virus has cleared—Can preclinical models be employed for Long COVID research?

Respiratory complications

Hamsters, mice, and monkeys have shown signs of long-term respiratory complications after infection by SARS-CoV-2. Ferret models, however, which are used for many studies into influenza, are not considered suitable for long Covid research as they develop only mild upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Common long-COVID symptoms are known to be correlated with an over-sustained immune response. Hamsters have shown persistence of immune response even after systemic removal of SARS-CoV-2. Because of long-term changes in the lungs and the olfactory tissues which are similar to human samples, hamsters could potentially be used for further mechanistic and interventional studies of long Covid.

Monkeys experience a sustained infiltration of immune cells in the lungs, as well as the presence of pneumonia and lung lesions after clinical Covid-19 recovery.

Humanised mice expressing human immune cells and human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) have exhibited persistent immune and inflammatory responses, the sustained presence of viral RNA, weight loss, and lung fibrosis 28 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection. This could make them a valuable model for the study of the aetiology of prolonged respiratory complications and, therefore, long Covid studies.

Multiorgan and systemic complications

Although a respiratory disease of the lungs, SARS-CoV-2 infection affects several other organ systems and an animal model is needed to represent its long-term multiorgan effects.

Human-ACE2-expressing mice, monkeys, ferrets, and hamsters could be used to study multiorgan complications of long Covid. In these animals, the presence of viral RNA has been observed in multiple organs outside the respiratory tract. In hamsters, progressive bone loss has also been observed 60 days after infection. Monkeys have been found to exhibit similar clinical manifestations and systemic immune responses as Covid-19 patients during the post-acute phase of infection and could be used to study the immune system-induced damage associated with long Covid.

Cardiovascular complications

Heart palpitations, chest pains, and myocarditis are common symptoms of long Covid. These heart-related dysfunctions could be studied in the hamster model, as hamsters have exhibited cardiovascular damage related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (ventricular wall thickening, increased ventricular mass/body mass ratio, and interstitial coronary fibrosis) up to 14 days post-infection. Humanized mice and monkeys could also be used to study cardiac complications as viral RNA has been detected in their heart tissues between five and six weeks post-infection. Determining the mechanisms of cardiovascular abnormalities will be essential for helping to identify who is most susceptible to long Covid, as well as how to treat it.

Neurological complications

Neuropsychiatric, neurological, and cognitive-related complications, including olfactory dysfunction, headaches, cognitive decline, depression, and anxiety, have been observed in long-Covid patients. Behavioural studies using animal models have the potential to provide critical insights into such complications, but finding an appropriate model has proved challenging.

Some promising results have been obtained from long-term studies in monkeys. However, data on neurological effects in monkeys following SARS-CoV-2 infection is still scarce, and more studies are needed to evaluate the usefulness of this model.

Studies investigating olfactory dysfunction and anosmia in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters have indicated that the virus causes severe damage to olfactory epithelium but function is rapidly restored soon after viral clearance. However, long-term effects have also been observed, notably a persistent disturbance in cognitive and behavioural activities. Hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 have been found to have a modified expression of specific genes in the brain which are usually activated during inflammation, one month after infection when the virus is no longer detectable. Behavioural studies have also shown that infected hamsters are les spontaneously active and have increased sensitivity to pain, resembling some of the neurological symptoms reported by patients, probably due to a continuing inflammation of the nervous system.

Studies in mice have shown similar results, exhibiting long-term inflammation in the brain after infection with SARS-CoV-2, even when the respiratory disease was mild and the virus was not detectable in the brain.

Both studies in hamster and mouse models have confirmed that some of the neurological manifestations of long Covid share molecular mechanisms with neurodegenerative disease, characterised by neuroinflammation and proteinopathy. Inflammation is accompanied by altered gene expression and accumulation of altered forms of two proteins, called tau and alpha-synuclein, in the brain two weeks after infection. The accumulation of modified tau and alpha-synuclein are characteristic findings in the brains of patients with neurodegenerative diseases (such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s).

There are still many unknowns surrounding long covid, and much to be uncovered. Given that none of the currently available animal models seems to fully replicate the condition, it seems sensible to continue using multiple models to study its different aspects. It is not an easy task: with so many factors to consider and such a wide range of possible outcomes, a great deal of complex and sensitive science is going to be needed.

Last edited: 15 April 2024 13:21