The Eurasian lynx was hunted to extinction in Britain soon after the Romans left; it’s time to bring it back.

The removal of border defences between Germany and the Czech Republic at the end of the cold war allowed Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) to move west into new hunting grounds in Bavaria. A re-wilding had begun. By 1992 there had been more than twenty sightings of lynx in the southern part of the Black Forest. Other re-introductions in Switzerland and France have contributed to the spread of lynx back into west Europe, but nowhere is it common, as you would expect with a solitary top predator that requires many square kilometres of range.

Until twenty years ago it was assumed lynx had died out in the UK long ago, either about 10,000 years ago, not long after the ice had retreated, or about 4000 years ago, as the region's climate turned cooler and wetter. Either way, climate was thought to be to blame, not people.

But in 1997 a lynx skull in the collections of the National Museums of Scotland was dated to around AD 240, during the Roman occupation of Britain. More lynx bones from the Craven caves in Yorkshire were dated between AD 425 and AD 600, proving the Lynx had hung on into the early medieval period.

And a carving on a 9th-century Pictish stone of a hunting scene has a cat-like figure with tufted ears, almost definitely a lynx.

So humans, not climate, wiped out the lynx in Britain, which I believe makes a case for bringing them back to the UK, a case made ever stronger as the crucial role of top carnivores in ecosystems becomes clearer.

We have a deer problem where roe deer and the non-native muntjac are preventing woodland regeneration. Deer are also destroying the understory layer where small birds like to nest. Their growth in numbers across the UK is partly because they do not have natural predators to control them.

While re-introducing wolves, another natural predator of deer, is politically difficult, lynx could seem to be an ideal predator for deer control as they are safe to man. Lynx are solitary animals; a secretive creature that prefers dense forests full of hiding places and stalking opportunities. Often the only way humans know lynx are around is by footprints in the snow.

The British lynx was most closely related to Northern European lynx so the UK Lynx trust aims to re-introduce lynx to Britain from a population of captive bred Eurasian lynx – once they have permission from the relevant authorities.

Scotland has enough woodland, and enough deer for around 450 lynx, while the woodlands of southern and southwest England could accommodate another 200 or so.

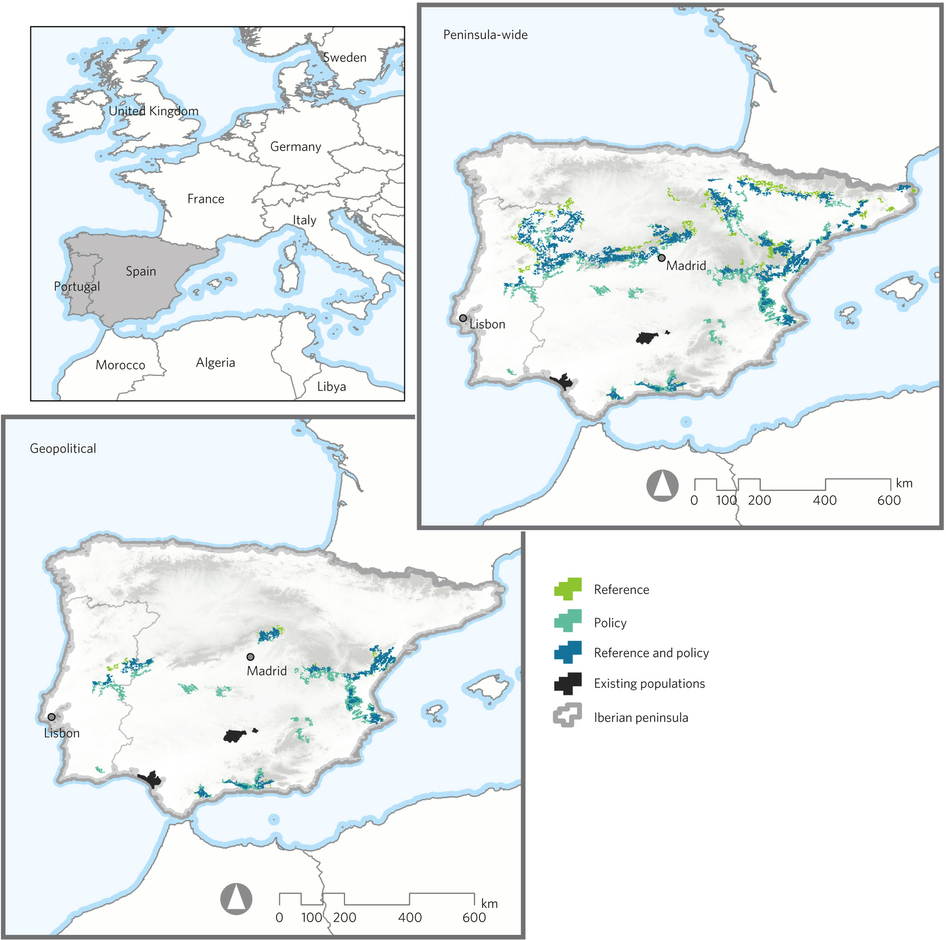

But while the Eurasian Lynx is unlikely to go extinct, its relative, the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus), is in real trouble. Heroic and last-minute efforts have brought the population back from below a hundred animals ten years ago to around 300 today, but the reserve areas set aside for this lovely animal in south Spain are changing. A paper in Nature argues the populations should be relocated to the north of Spain, where rainfall should remain sufficient to provide the plants that the Iberian lynx key prey – rabbits – need. This proposal is reasonable as the Iberian lynx range once extended into southern France.

If the Iberian lynx were to become extinct, it would be the first big cat species to do so since the sabre-toothed Smilodon, some 10,000 years ago, a grim prospect. The population is still incredibly vulnerable. A virus disease in rabbits has decimated the available prey and Iberian lynx are themselves vulnerable to TB.

As man is forced to micro-manage threatened species and their habitats to try and ensure their survival it is perhaps time to consider more radical moves.

The south of Britain is full of rabbits so perhaps a population of Iberian lynx should be introduced here. If southern England can theoretically support 200 Eurasian lynx it should be able to support at least that number of Iberian Lynx – a number that is just about enough for a genetically viable population.

During my lifetime, otters have rebounded, beavers are being reintroduced and the Eurasian Lynx is being considered – why not the Iberian Lynx as well?

More rewilding: http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/08/bring-back-big-cats-it-time-start-rewilding-britain

Last edited: 28 October 2022 14:57