Mice are the most used animals in scientific research in Great Britain. They have paved the way for biomedical discoveries since the 17th century. But mouse behaviour has not been well understood for much of that time and it is only relatively recent studies that have revealed what makes a mouse anxious, and how that anxiety can be reduced.

A history of mouse models

Today, over 400 inbred mouse strains live in laboratories across the world. Most of them have stemmed from the careful selection of a handful of mice by mouse fanciers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Asia and, later, Europe and America. Many inbred strains we know today derive from the colonies of Miss Abbie Lathrop, a mouse fancier who bred and sold mice from her small white farmhouse in Granby, Massachusetts, from around 1900 to her death in 1918.

Often portrayed as an eccentric hobbyist who was oddly attracted to mice, Lathrop was not only an avid mouse breeder she was also a savvy business woman and a self-made scientist. Lathrop' careful and methodical mouse breeding helped advance modern cancer research and create a standard organism of science. In 1902, her mice became the first to be used in a lab for genetic research—and some still are today. The mice Lathrop started breeding more than a century ago have gone on to be part of life-saving research.

It is undeniable that these mice have revolutionised science. And although laboratory mice have been genetically divorced from their natural cousins for quite some time now, comparing them has led to indisputable improvements in the understanding of these animals and to refinements in the ways they are kept in captivity.

Studying wild mice to inform captive conditions

Professor Jane Hurst, University of Liverpool, has been studying mouse behaviour and animal welfare for nearly four decades. She has worked with wild mice, brought into labs, to better understand these animals and figure out why these rodents are so successful in nature.

“Studying wild rodent colonies in captivity has given me insights into what these animals normally do and good ways to keep them in captivity,” she told UAR. “I’m an animal behaviourist, so I'm interested in what the animals do. And from that, I’ve been asked to advise the community about better ways to keep rodents - to look at the welfare of laboratory rodents from the perspective of what these animals would normally need and choose to do.”

Much of Jane Hurst’s work has led to better welfare standards for laboratory mice. Part of that meant adapting the laboratory environment to the mice so it would better mimic their natural setting. She installed for example reverse lighting conditions to study the animals when they were most active – at night. At the time, this was not typical for most laboratories. A few people got curious of the way she was doing things. And in the early 1990s, she was asked to look at some housing conditions to see what she thought of them.

“I asked myself what would be the one thing I would do to improve mouse welfare in labs? And it was very obvious to me that it was the way people handled the rodents – which was very different from the way we were doing things,” She told UAR. “I knew that if I approached wild mice in the way that people approached laboratory mice, there was no way I was ever going to see any natural behaviour because they would just be so stressed.”

Minimising stress during handling

In the early 2000s, Jane Hurst started looking into the handling methods and the stress it caused mice in laboratories.

“At the time, researchers were looking into the lack of reproducibility of studies,” Hurst explains. “From what I was reading, the response to stress was involved, and it seemed fairly obvious to me that a lot of that stemmed from the way the animals were interacting with different people.”

After studying different handlers (males, females, experienced, novices) using different handling methods, the latter turned out to be the determining stress factor rather that the person doing the handling. In effect, the traditional ‘picking up of mice by the tail’ was causing a major source of stress to the animals that induced strong aversion to the handler to the point that the animals were exhibiting abnormal behaviours, skewing scientific behavioural observations but also biomedical parameters linked to stress (hormones etc.).

Indeed, background stress and anxiety can be confounding factors in many areas of scientific research. Minimising such responses, not only has a beneficial effect for the mice but also reduces variability and thus improve the reliability of data generated. It became clear that something had to be done to reduce the anxiety in the animals in contact with humans.

Non-aversive handling methods

When working with wild rodents, Jane had refined her interactions with the animals to avoid as much direct handling as possible.

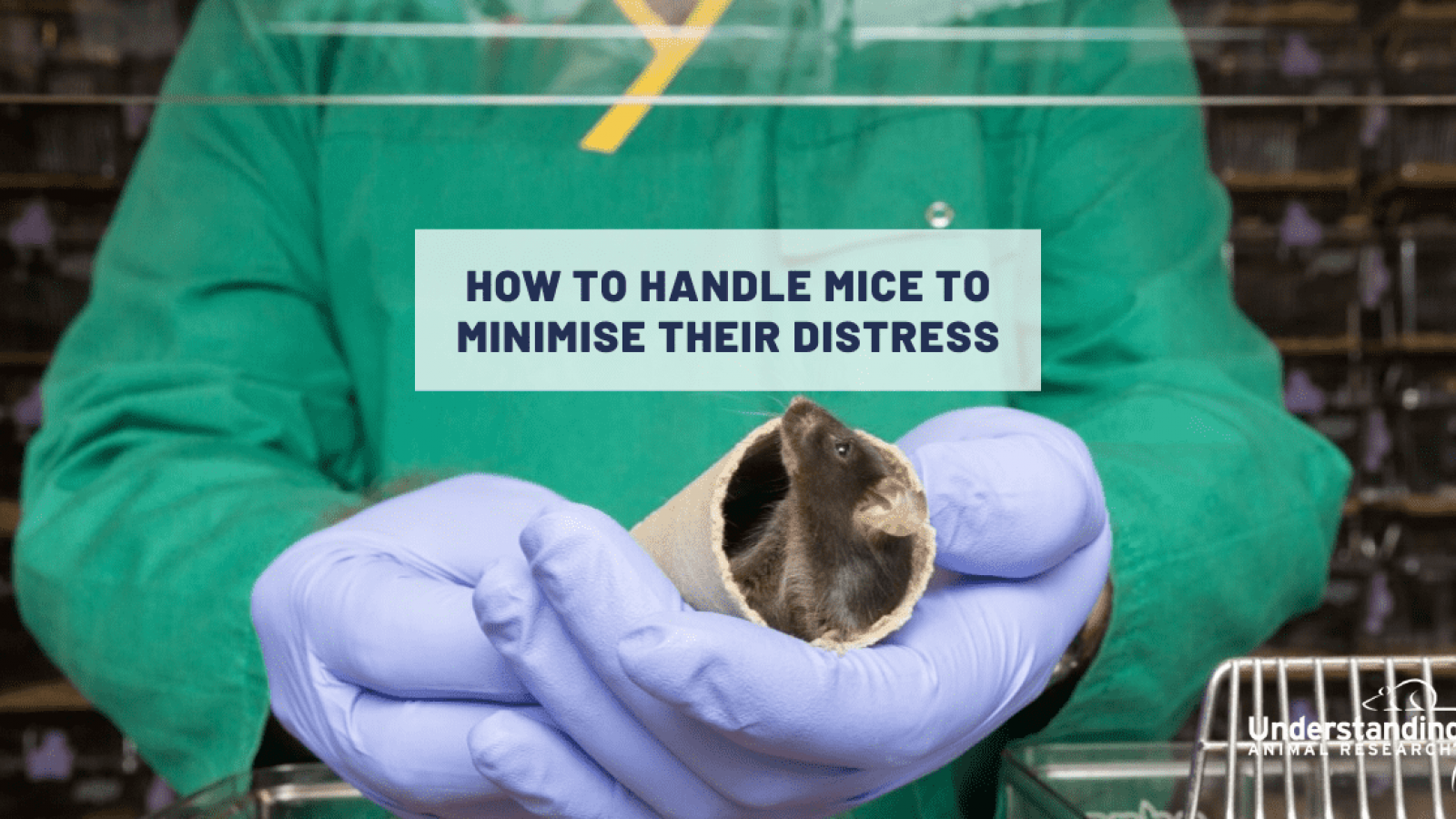

“I had a lot of free-ranging rodents in enclosures and it was difficult to get hold of them. I had habituated and trained my mice to be indirectly handled using tunnels they would naturally be attracted to for safety. It was a much faster and much less stressful way to handle them, both for the mice and for the handler. You didn’t need to chase them around anymore, you could just get them in a safe-feeling clear tunnel.”

It turned out that even picking up the domesticated tame mice using cupped hands was much less stressful to the animals than by the tail. “It made a big difference to the animals. At first nobody believed this was even an issue, but we got solid scientific data using different strains of mice to back our claims. We’ve been working for the last 12 years to show that this is a very general and solid effect,” explains Jane Hurst.

Changing practice in labs

After the scientific facts were established, it took unfortunately a bit more time than planned to change the general practice. The collaboration with the NC3Rs was key to bringing this data to the right audience.

“It is not always easy to change people’s habits, but with the right convincing and proof, we are changing the landscape one person at the time,” adds Jane Hurst.

Recognising the benefits for animal welfare and science, many UK establishments have now switched to tunnel handling or cupping as part of their commitment to the 3Rs and a culture of care.

As well as a thoroughly documented evidence in scientific publications, different resources are available to help implement these non-aversive mouse handling methods, including video tutorials and frequently asked questions, that can be found on the NC3Rs’ How to pick up a mouse hub.

Last edited: 21 June 2023 15:31