Members of Parliament have research staff and a dedicated library which they can use to get accurate information on all areas of policy. So it is a bit frustrating that so many of them rely instead on campaign groups, many of which trade heavily in myths rather than facts.

So it was with a recent Westminster Hall debate. It was to consider a public petition supposedly on banning commercial breeding for animal testing and establishing a committee for new approach methodologies, usually known as NAMs, but was itself based on a poor understanding of the existing regulatory system that requires the use of animal alternatives where they exist.

Unfortunately, the debate was no better informed. MPs wondered aloud about things that would have been trivially easy for their researchers to enlighten them on. Some couldn’t fathom the reasons for a 6% increase in animal tests the year after a global lockdown had caused a 15% decrease in animal tests. One MP, who had previously condemned violence against MPs, hailed as ‘heroes’ the people who had stalked a young family, planted an explosive device and thrown a brick at the windscreen of a moving car driven by animal care staff. Two MPs thought a study on drug-seeking behaviour relating to vaporized cannabis was all about giving rats the munchies. Yet another thought that penicillin had been delayed for ten years by animal experiments, making them slightly less knowledgeable on this point than any school child who has visited the Science Museum and seen the exhibit there on the history of penicillin.

The MPs had chosen as sources of information organisations which either don’t know how things work, or do know and are lying for effect. They had the crucial facts wrong. Here are eight of the most egregious pieces of misinformation that were on display at the debate, and what the MPs would have found out if they had asked anyone who understood the issues.

Myth 1: Medical research is NAMs vs animals

The biosciences are built on three essential pillars: research on the lab bench; research in humans; and research in animals. New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) complement, enhance and might soon supersede some existing animal and/or current non-animal methods, but are mostly still in development. Many are limited in scope, for instance predicting only one effect in one organ, but can perform very well within their limits. NAMs can perform better than animal studies in areas where animal models are at their weakest, but do not outperform animal models where they are at their strongest. This means that NAMs are extremely useful as a new tool, and they may be the future of many areas of research, but they won’t completely replace existing methods in the short to medium term any more than email replaced the need for a postal service in 2005.

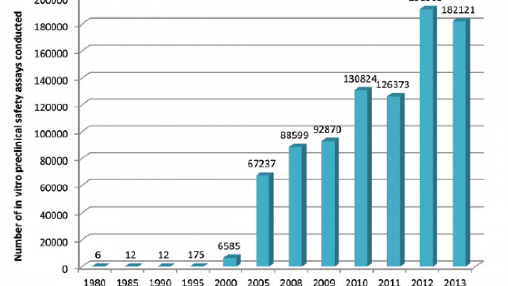

The pharma industry has been using alternatives as they become available, starting in 1980 but rising exponentially after the year 2000

Source: Goh et al, Toxicol. Res., 2015,4, 1297-1307

The biosciences use NAMs already. They were adopted at the earliest opportunity. Some, like liver-on-a-chip technology, should now be considered as part of the standard battery of drug safety tests based on data collected late last year. It is estimated that using a liver chip right at the start of the research process could identify problems in around 9 per 100 candidate drugs – 3 per year in the UK, early enough to prevent wasting time, resources and animals on their further development.

However, many tools such as computer models are still in development and much less developed than the liver on a chip. There are also qualifications, such as that this is low-hanging fruit since liver toxicity is one of the main causes of the failure of new drugs in human trials. This was also a first-of-its-kind study, despite the claims of activists that such NAMs are evaluated and ready to use. We would expect rapid gains in terms of experiments avoided and lower costs for pharma companies as chips for other systems are developed, validated and applied, followed by a sharp tail-off as the problems get harder to model outside of a living organism. Databases of NAMs, their applications and their limitations are maintained by organisations like the OECD as first port of call for researchers and the fact there are drug safety regulations later on doesn’t stop pharma companies from just using NAMs now, so they do!

Absolutely nobody is opposed to their use and animals are not used at the expense of NAMs – in fact the law in the UK is very clear that animals may not be used if a non-animal method could be used instead.

Myth 2: Animals don’t predict human effects in drug trials

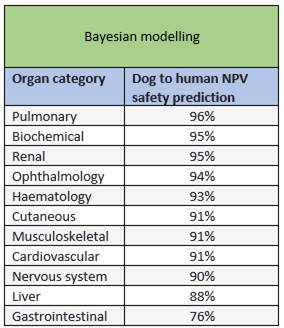

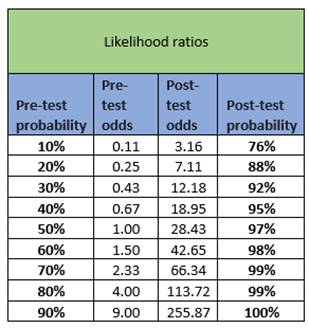

The best data on drug testing shows that animals predict human safety 86% of the time across all species in drug testing. Dogs predict it 91% of the time on average, and up to 96% depending on the target organ.

We should be clear, though, that ‘safe’ is being used in a very specific way here. It means ‘safe enough to try in humans’, not ‘This will be safe when given to 10,000 people’. The point of preclinical tests isn’t to generate a binary safe/unsafe prediction but to gain enough data to support a decision couched in caveats and confidence intervals about whether we should advance towards human testing and if so to help design a safer clinical trial. For instance, data from the animal and non-animal tests might influence the dosing regime for human volunteers to minimise risk of liver damage. It is not expected to eliminate risk altogether. If it did, we would have no need of phase 1 human trials.

Animals are very good at predicting phase 1 human safety.

Sources: Bayesian modelling: Q Consortium Translational database Likelihood ratios: Data from Bailey et al , 2014 I

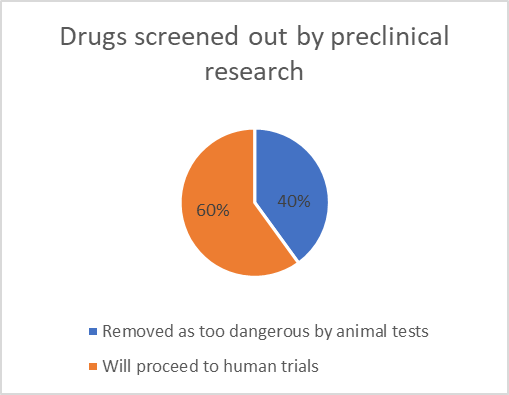

Around 40% of potential new drugs are screened out as too dangerous, mainly by preclinical tests in animals. With about 89 Phase 1 trials in the UK each year, consisting of an average of 25 volunteers, this equates to nearly 900 humans protected from death or serious injury each year as a direct result of the animal safety tests.

When it comes to basic biological research – research into understanding how bodies and diseases work – things get even more complicated. It typically takes decades for the therapeutic relevance of basic research findings to reveal themselves. The first ‘curiosity based’ discoveries behind mRNA vaccines, for instance, were made in the late 1970s and have been built upon each decade since. This ‘curiosity science’ only found a clinical application 37 years after the initial discoveries. However, it now seems likely that these mRNA technologies, that have already been so important in the development of COVID-19 vaccines, will be instrumental in treating cancer and HIV.

Myth 3: 90% of new medicines fail to pass human trials because animals cannot predict human responses

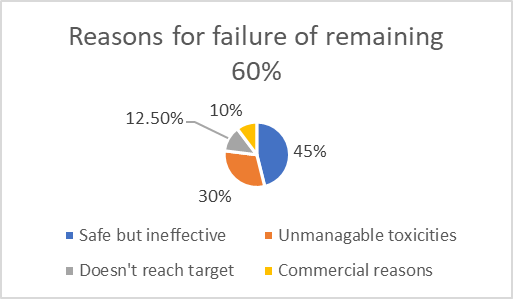

90% of medicines fail during clinical trials but it has nothing to do with the animal tests. Of every 100 new chemical entities (NCEs), 40% are considered too dangerous to test in humans following tests on animals, tissue samples, human blood products etc.

However, of those going forward, many will have shown effects in the animal and non-animal tests that hint at side-effects that may or may not be manageable through things like careful dosing. It’s the job of the human trial to find out if it can be done. During human trials, some 94% of new drugs are eliminated. 40-50% fail because they are safe (which the animal test was for) but not effective (which the animal test was not for).

30% fail because they have suspected toxicities that do indeed turn out to be too much for patients to tolerate, 10-15% because the drug fails to travel around the body properly and 10% because of commercial reasons.

It’s worth noting that ‘failures’ occur across all three stages of clinical trial, so drugs that fail in humans have usually already passed some human tests.

Image 1 source: An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14, 475–486 (2015).

Image 2 source: Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?

In short, animals in medicines testing have predicted what we wanted them to predict very well, i.e. whether a drug will be safe enough to attempt in humans. Everything else is a shortcoming of the drug development system overall.

Myth 4: Penicillin was delayed by a decade by disappointing animal data

Complete fiction. Alexander Fleming – the discoverer of penicillin – struggled both to generate interest in his discovery and to purify penicillin in the quantities needed to test it. Several attempts were made to purify it by the UK’s leading chemists during the 1930s, including Prof Harold Raistrick at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine but none were successful.

A team led by Florey and Chain, looking for antibiotics to help the war effort in 1940, identified penicillin as having untapped potential if the purification problem could be overcome. Team member Norman Heatley did this by inventing a new process of back-extraction, but even then, the quantities produced weren’t enough to treat even one person. The team approached the US Dept of Agriculture research lab in Illinois, skilled at fermenting corn starch, which found ways of making the effects of penicillin far more potent using fermentation and a better strain of mould. It could also ramp up the scale of production so that a dose was available for all soldiers during the D-Day landings.

A team led by Florey and Chain, looking for antibiotics to help the war effort in 1940, identified penicillin as having untapped potential if the purification problem could be overcome. Team member Norman Heatley did this by inventing a new process of back-extraction, but even then, the quantities produced weren’t enough to treat even one person. The team approached the US Dept of Agriculture research lab in Illinois, skilled at fermenting corn starch, which found ways of making the effects of penicillin far more potent using fermentation and a better strain of mould. It could also ramp up the scale of production so that a dose was available for all soldiers during the D-Day landings.

The story of how this was done has been the subject of books, radio plays and was turned into a movie starring Hollywood star Dominic West in 2011. Artefacts from the time sit in London’s Science Museum. It is not some unknown period in medical history.

"The story of penicillin" - The Science Museum

"Norman Heatley, the Unsung Hero who developed penicillin" - BBC News There is literally a film about this...

Myth 5: Researchers don’t consider the 3Rs.

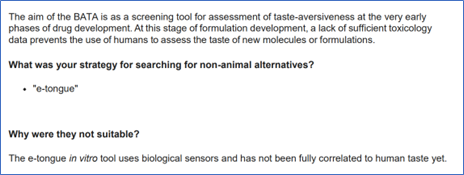

At one point in the debate, an MP claimed that researchers did not show proper consideration for the 3Rs of reduction, replacement and refinement of experiments. The evidence for this was the claim that in applications for animal research licences, some researchers provided glib one-word answers to the question asking them to describe their strategy for looking for non-animal alternatives. Could this be true?

The Home Office publishes all animal experiments on its website so it’s possible to check. Out of more than 400 ‘non-technical summaries’ of experiments, there was only one that had a one-word answer to the question about strategies for finding non-animal methods. But the answer was surrounded by 1,084 other words on the same topic under 12 related headings.

The Home Office publishes all animal experiments on its website so it’s possible to check. Out of more than 400 ‘non-technical summaries’ of experiments, there was only one that had a one-word answer to the question about strategies for finding non-animal methods. But the answer was surrounded by 1,084 other words on the same topic under 12 related headings.

The offending one-word answer was ‘e-tongue’. The next question asked why the proposed alternative wasn’t suitable:

Why were they not suitable?

The e-tongue in vitro tool uses biological sensors and has not been fully correlated to human taste yet.

What more could there be to say?

Source Non-technical summaries for project licences granted during 2020, page 692.

Myth 6: The Home Office doesn’t refuse many licences for experiments

Procuring a licence to conduct animal work is a back-and-forth process, first between the ethical review bodies and the researcher, and then between the researcher and the Animals in Science Regulation Unit (ASRU) of the Home Office. The Home Office may well send applications back with tens of amendments to be made and questions to be answered before a licence can be granted. This happens over all three tiers of ethical review and researchers may simply withdraw their application as a result of the challenge. The fact a licence is eventually granted doesn’t mean that all submitted applications are waved through and it is certainly untrue that applicants are always successful first time.

Myth 7: The BMJ/FDA/ National Cancer Institute think animal models don’t work

There are a number of quotations from figures who have represented prestigious scientific organisations that seem to imply that they oppose the use of animals in research. Such quotes are usually taken out of context and tend to be dated, often referring to issues in translating medicines to humans that have since been overcome. No serious scientific publication or institution thinks animal experiments can’t work if conducted properly.

Dr Richard Klausner, the former director of the US National Cancer Institute did indeed say ‘We have cured mice of cancer for decades, and it simply didn't work in humans.’ It was in reference to a new class of drugs that he also described as ‘the single most exciting thing on the horizon’ for cancer treatment, based on the animal data. It was clumsy language, not some official position. Did the drugs ultimately work? Yes. We have aflibercept, sunitinib, sorafenib, axitinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib and ramucirumab as a result so, despite Klausner’s orphaned comment, it simply did work.

The BMJ did indeed feature an editorial questioning the translation of poorly designed and reported studies to the clinic. It did not damn well-designed and reported studies.

The FDA in fact describes animal models as ‘critically needed’ and has a whole program for developing them: Animal Model Qualification Program.

Myth 8: The safety of drugs is based on animal data only

Human drugs are tested on humans through three stages of human trial and an unofficial ‘stage 4’ which follows their licencing for use by doctors who then record adverse reactions and public reports though the MHRA yellow card system so that effects only observable in population-level cohorts of people can be detected. This didn’t stop one MP from claiming that ‘Vioxx, relying solely on its results when tested on monkeys, resulted in the deaths of, and injuries to, nearly 8,000 people’, which is simply untrue.

There’s a reason why even the Wikipedia page on Vioxx doesn’t even mention animals and focuses instead on the well-publicised manipulation of the human clinical trial data. This attempt to claim that humans are harmed by animal data, despite the fact that all approved drugs have been tested on thousands of other humans, is quite a common meme among activists but the only people that could ever be hurt by failing research methods would be clinical trial volunteers and particularly those in phase 1. Animal data are not used in isolation – the other activist favourite, TGN 1412, was also tested on human blood and tissue. It’s true that the animal model could have been improved. Even something which works nine times out of ten will sometimes fail, but any safety failure is a systemic one.

Scientists and voters deserve better.

As the philosopher Edmund Burke once argued, MPs aren’t simply a delegate for an area, but people who will have to exercise their own judgement in a leadership role. Indeed, they will not be able to represent all of their constituents all of the time since they will hold opposing views and may not be in possession of the facts. Hence Burke wrote,

‘Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.’ - Speech to the electors of Bristol, 1774

In failing to understand how animals fit into the research process, MPs fail their constituents. If it hadn’t been for the ‘curiosity-based’ animal research scorned by certain MPs, we wouldn’t have had the AstraZeneca vaccine for COVID-19. If it weren’t for specialist lab animal breeders there would be far greater animal suffering. If animals weren’t used to safety screen drugs, about 900 Brits would be killed or seriously injured in phase 1 clinical trials each year.

NAMs are undoubtedly a big part of the future, but we happen to live in the present and millions of lives rely on MPs taking their time to seek the accurate information they need to serve their constituents, and country, to a satisfactory standard.

Last edited: 9 September 2025 11:35