Chris Magee, Head of Policy and Media, delves deeper into the 2013 statistics to look at some of the less mentioned trends in the use of animals in research. While animal research has been rising overall over the last two decades, this trend is far from uniform across different research areas.

The Annual Home Office statistics on the use of animals in research were released this week, to the usual controversy.

The Dr Hadwen Trust called for the phasing out of animal experiments, the National Anti-Vivisection Society was ‘dismayed’ and the BUAV claimed “The government has now failed for a third year on its 2010 post-election pledge to work to reduce the number of animals used in research.”

Actually, the Government haven’t failed in this regard at all, as there was a reduction in the number of animals used in experiments in 2013 of 15,552 – the BUAV got the number of animals confused with the number of procedures. This is relatively easy to do – the annual stats can be both cumbersome and confusing.

However, they can also yield some interesting gems. Most of us are aware of the boom in breeding genetically altered mice, which in 1995 made up 300,000 procedures, but today constitutes some 2.1 million of the UK’s 4.1 million annual procedures. Yup. Over half of what we’d think of as experiments are now breeding animals. The rise in genetically altered animals is allowing researchers to understand more about what our genes do, as well as allowing them to create better models of human diseases.

There are other findings such as the fact that fundamental biological research – simply attempting to find out how biological systems work – has increased by 800,000 to about 1.2 million. Similarly, procedures for cancer research have doubled to more than half a million. Government departments and other public bodies have doubled the amount of research they conduct to a combined total of some 600,000 procedures. The following graph illustrates some of the trends in animal research between 1995 and 2013 (The graph does not show all animal procedures, and some procedures will be included in multiple lines on the graph).

There have been significant decreases too: applied studies - using an animal to study human medicine - have halved since 1995, from over a million procedures to just over half a million, this likely reflects the increasing amount of translational work being carried out using non-animal methods - though this will only take the research so far, and at some point, it is likely an animal model will be needed. Similarly, using an animal for education has dropped by 5 times from 7,000 procedures to just 1,400.

Meanwhile, procedures for pharmaceutical R&D have halved since 1995 to less than a quarter of a million, and those for cosmetics, household products and tobacco have ceased completely. Since 1995 toxicology tests to satisfy regulatory purposes have fallen by almost 50% from 559,800 to 345,100 – this likely reflects the increased use of non-animal methods to complement and replace some animal tests

Overall, there are more decreases than increases in terms of non-breeding procedures. It would seem like many of the decreases listed above have been effectively hidden by the boom in the breeding of genetically manipulate animals, mainly GM Mice, to the extent that there was a 5% drop in non-breeding experiments in 2013.

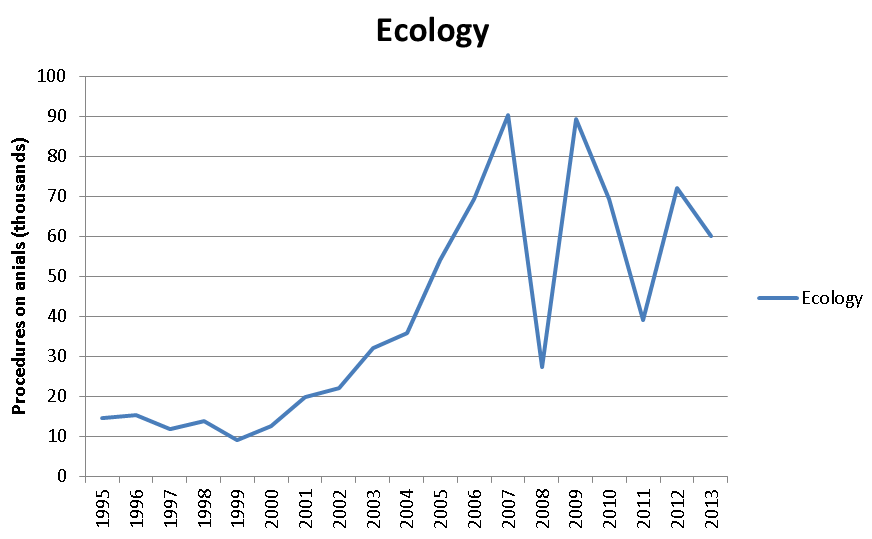

Not all of the trends are easy to explain. I literally have no explanation for what's going on with ecology research for instance, but procedures do seem to be rising on aggregate.

On the day of the stats release, we are generally running around myth-busting, explaining the stats to members of the public and making media appearances. However, they are worth spending more time with to spot the longer-term trends within UK animal research.

Last edited: 16 August 2022 14:37